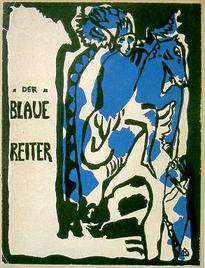

Der Blaue Reiter

Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) was a group of artists and a designation by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc for their exhibition and publication activities, in which both artists acted as sole editors in the almanac of the same name (first published in mid-May 1912). The editorial team organized two exhibitions in Munich in 1911 and 1912 to demonstrate their art-theoretical ideas based on the works of art exhibited. Traveling exhibitions in German and other European cities followed. The Blue Rider disbanded at the start of World War I in 1914.

The artists associated with Der Blaue Reiter were important pioneers of modern art of the 20th century; they formed a loose network of relationships, but not an art group in the narrower sense like Die Brücke (The Bridge) in Dresden. The work of the affiliated artists is assigned to German Expressionism.

History

[edit]

The forerunner of The Blue Rider was the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (N.K.V.M: New Artists' Association Munich), instigated by Marianne von Werefkin, Alexej von Jawlensky, Adolf Erbslöh and German entrepreneur, art collector, aviation pioneer and musician Oscar Wittenstein. The N.K.V.M was co-founded in 1909 and Kandinsky (as its first chairman) organized the exhibitions of 1909 and 1910. Even before the first exhibition, Kandinsky introduced the so-called "four square meter clause" into the statutes of the N.K.V.M due to a difference of opinion with the painter Charles Johann Palmié; this clause would give Kandinsky the lever to leave the N.K.V.M in 1911. In 1911, Palmié allowed Kandinsky and Marc to leave the association and organize the first Blue Rider exhibition. The Blue Rider was thus a spin-off from the N.K.V.M.[citation needed]

When there were repeated disputes among the conservative forces in the N.K.V.M, which flared up due to Kandinsky's increasingly abstract painting, he resigned the chairmanship on 10 January 1911 but remained in the association as a simple member. His successor was Adolf Erbslöh. In June, Kandinsky developed plans for his activities outside of the N.K.V.M. He intended to publish a "kind of almanac" which could be called Die Kette (The Chain). On 19 June, he pitched his idea to Marc and won him over by offering him the co-editing of the book.[citation needed]

The name of the movement is the title of a painting that Kandinsky created in 1903, but it is unclear whether it is the origin of the name of the movement as Professor Klaus Lankheit learned that the title of the painting had been overwritten.[1] Kandinsky wrote 20 years later that the name is derived from Marc's enthusiasm for horses and Kandinsky's love of riders, combined with a shared love of the color blue.[1] For Kandinsky, blue was the color of spirituality; the darker the blue, the more it awakened human desire for the eternal (as he wrote in his 1911 book On the Spiritual in Art).

Within the group, artistic approaches and aims varied from artist to artist; however, the artists shared a common desire to express spiritual truths through their art. They believed in the promotion of modern art; the connection between visual art and music; the spiritual and symbolic associations of color; and a spontaneous, intuitive approach to painting. Members were interested in European medieval art and primitivism, as well as the contemporary, non-figurative art scene in France. As a result of their encounters with Cubist, Fauvist and Rayonist ideas, they moved towards abstraction.[citation needed]

Der Blaue Reiter organized exhibitions in 1911 and 1912 that toured Germany. They also published an almanac featuring contemporary, primitive and folk art, along with children's paintings. In 1913, they exhibited in the first German Herbstsalon.[citation needed]

The group was disrupted by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Franz Marc and August Macke were killed in combat. Wassily Kandinsky returned to Russia, and Marianne von Werefkin and Alexej von Jawlensky fled to Switzerland. There were also differences in opinion within the group. As a result, Der Blaue Reiter was short-lived, lasting for only three years from 1911 to 1914.[citation needed]

In 1923, Kandinsky, Feininger, Klee and Alexej von Jawlensky formed the group Die Blaue Vier (The Blue Four) at the instigation of painter and art dealer Galka Scheyer. Scheyer organized Blue Four exhibitions in the United States from 1924 onward.

An extensive collection of paintings by Der Blaue Reiter is exhibited in the Städtische Galerie in the Lenbachhaus in Munich.[citation needed]

Almanac

[edit]

Conceived in June 1911, Der Blaue Reiter Almanach (The Blue Rider Almanac) was published in early 1912 by Piper in an edition that sold approximately 1100 copies; on 11 May, Franz Marc received the first print. The volume was edited by Kandinsky and Marc; its costs were underwritten by the industrialist and art collector Bernhard Koehler, a relative of Macke. It contained reproductions of more than 140 artworks, and 14 major articles. A second volume was planned, but the start of World War I prevented it. Instead, a second edition of the original was printed in 1914, again by Piper.[2]

The contents of the Almanac included:

- Marc's essay "Spiritual Treasures," illustrated with children's drawings, German woodcuts, Chinese paintings, and Pablo Picasso's Woman with Mandolin at the Piano[3]

- an article by French critic Roger Allard on Cubism

- Arnold Schoenberg's article "The Relationship to the Text", and a facsimile of his song "Herzgewächse"

- facsimiles of song settings by Alban Berg and Anton Webern

- Thomas de Hartmann's essay "Anarchy in Music"

- an article by Leonid Sabaneyev about Alexander Scriabin

- an article by Erwin von Busse on Robert Delaunay, illustrated with a print of his The Window on the City

- an article by Vladimir Burliuk on contemporary Russian art

- Macke's essay "Masks"

- Kandinsky's essay "On the Question of Form"

- Kandinsky's "On Stage Composition"

- Kandinsky's The Yellow Sound.

The art reproduced in the Almanac marked a dramatic turn away from a Eurocentric and conventional orientation. The selection was dominated by primitive, folk and children's art, with pieces from the South Pacific and Africa, Japanese drawings, medieval German woodcuts and sculpture, Egyptian puppets, Russian folk art, and Bavarian religious art painted on glass. The five works by Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Gauguin were outnumbered by seven from Henri Rousseau and thirteen from child artists.[4]

Exhibitions

[edit]

First exhibition

[edit]On December 18, 1911, the First exhibition of the editorial board of Der Blaue Reiter (Erste Ausstellung der Redaktion Der Blaue Reiter) opened at the Heinrich Thannhauser's Moderne Galerie in Munich, running through the first days of 1912. 43 works by 14 artists were shown: paintings by Henri Rousseau, Albert Bloch, David Burliuk, Wladimir Burliuk, Heinrich Campendonk, Robert Delaunay, Elisabeth Epstein, Eugen von Kahler, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter, Jean Bloé Niestlé and Arnold Schoenberg, and an illustrated catalogue edited.[5]

From January 1912 through July 1914, the exhibition toured Europe with venues in Cologne, Berlin, Bremen, Hagen, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Budapest, Oslo, Helsinki, Trondheim and Göteborg.[6]

Second exhibition

[edit]From February 12 through April 2, 1912, the Second exhibition of the editorial board of Der Blaue Reiter (Zweite Ausstellung der Redaktion Der Blaue Reiter) showed works in black-and-white at the New Art Gallery of Hans Goltz (Neue Kunst Hans Goltz) in Munich.[7]

Other shows

[edit]The artists of Der Blaue Reiter also participated in these other exhibitions:

- 1912 Sonderbund westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler exhibition, held in Cologne

- Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon (organised by Herwarth Walden and his gallery, Der Sturm), held in 1913 in Berlin

Members

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Vezin, 1992, p. 124

- ^ Katharina Erling: Der Almanach Der Blaue Reiter, in: Hopfengart (2000, pp. 188-239

- ^ Peter Nicholls, Modernisms: A Literary Guide, Berkeley, CA, University of California Press, 1995; p. 141.

- ^ George Heard Hamilton, Painting and Sculpture in Europe, 1880–1940, New Haven, CT, Yale University Press, 1993; pp. 215-16.

- ^ Catalogue, reproduced in Hoberg & Friedel (1999), pp. 364-365.

- ^ Ortrud Westheider et alt.: Die Tournee der ersten Ausstellung des Blauen Reiters, in: Christine Hopfengart (2000), pp. 49-82

- ^ Catalogue?

References

[edit]- John E. Bowlt, Rose-Carol Washton Long. The Life of Vasilii Kandinsky in Russian art: a study of "On the spiritual in art" by Wassily Kandinsky. Pub l. Newtonville, Mass. USA. 1980. ISBN 0-89250-131-6 ISBN 0-89250-132-4

- Wassily Kandinsky, M. T. Sadler (Translator) Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Dover Publ. (Paperback). 80 pp. ISBN 0-486-23411-8. or: Lightning Source Inc. Publ. (Paperback). ISBN 1-4191-1377-1

- Shearer West (1996). The Bullfinch Guide to Art. UK: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 0-8212-2137-X.

- Hoberg, Annegret, & Friedel, Helmut (ed.): Der Blaue Reiter und das Neue Bild, 1909-1912, Prestel, München, London & New York 1999 ISBN 3-7913-2065-3

- Hopfengart, Christine: Der Blaue Reiter, DuMont, Cologne 2000 ISBN 3-7701-5310-3

- Vezin, Annette; Vezin, Luc (1992). Kandinsky and the Blue Rider. Terrail. ISBN 978-2-87939-043-7.

External links

[edit] Media related to Der Blaue Reiter at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Der Blaue Reiter at Wikimedia Commons- Collection: "Expressionism–Der Blaue Reiter" from the University of Michigan Museum of Art