Morbillivirus

| Morbillivirus | |

|---|---|

| |

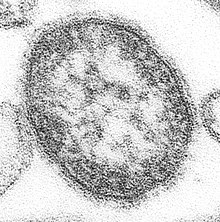

| Morbillivirus hominis electron micrograph | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Monjiviricetes |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Paramyxoviridae |

| Subfamily: | Orthoparamyxovirinae |

| Genus: | Morbillivirus |

| Species | |

Morbillivirus is a genus of viruses in the order Mononegavirales, in the family Paramyxoviridae.[1][2] Humans, dogs, cats, cattle, seals, and cetaceans serve as natural hosts. This genus includes six species, with a seventh species being extinct. Diseases in humans associated with viruses classified in this genus include measles; in animals, they include acute febrile respiratory tract infection and Canine distemper.[3] In 2013, a wave of increased death among the Common bottlenose dolphin population was attributed to morbillivirus.[4]

Genus

[edit]| Genus | Species | Virus (Abbreviation) |

| Morbillivirus | Morbillivirus canis | Canine distemper virus (CDV) |

| Morbillivirus caprinae | Peste-des-petits-ruminants virus (PPRV) | |

| Morbillivirus ceti | Cetacean morbillivirus (CeMV) | |

| Morbillivirus felis | Feline morbillivirus (FeMV) | |

| Morbillivirus hominis | Measles virus (MeV) | |

| †Morbillivirus pecoris | Rinderpest virus (RPV) | |

| Morbillivirus phocae | Phocine distemper virus (PDV) |

Structure

[edit]

Morbillivirions are enveloped, with spherical geometries. Their diameter is around 150 nm. Genomes are linear, around 15–16 kb in length. The genome codes for eight proteins.[2][3]

| Genus | Structure | Symmetry | Capsid | Genomic arrangement | Genomic segmentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morbillivirus | Spherical | Enveloped | Linear | Monopartite |

Life cycle

[edit]Viral replication is cytoplasmic. Entry into the host cell is achieved by virus attaching to host cell. Replication follows the negative-stranded RNA virus replication model. Negative-stranded RNA virus transcription, using polymerase stuttering, through co-transcriptional RNA editing is the method of transcription. Translation takes place by leaky scanning. The virus exits the host cell by budding. Humans, cattle, dogs, cats, and cetaceans serve as the natural hosts. Infection from this virus takes place in five stages: incubation, prodromal, mucosal, diarrheic, and convalescent.[6][7] Transmission routes are respiratory.[2][3][8][9][10] Morbillivirus are sensitive to high temperatures, sunlight, extreme pH levels, and any chemical that can destroy its outer envelope.[11]

| Genus | Host details | Tissue tropism | Entry details | Release details | Replication site | Assembly site | Transmission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morbillivirus | Humans, dogs, cats, cetaceans | None | Glycoprotein | Budding | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Aerosols |

References

[edit]- ^ Rima B, Balkema-Buschmann A, Dundon WG, Duprex P, Easton A, Fouchier R, et al. (December 2019). "ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Paramyxoviridae". The Journal of General Virology. 100 (12): 1593–1594. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.001328. PMC 7273325. PMID 31609197.

- ^ a b c "Family: Paramyxoviridae". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).

- ^ a b c "Morbillivirus". Viral Zone. ExPASy. taxid:11229. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Jackson H (19 November 2014). "Virus causing Atlantic dolphin die-off". The Daily Times. p. T11. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Kuhn JH, Abe J, Adkins S, Alkhovsky SV, Avšič-Županc T, Ayllón MA, et al. (August 2023). "Annual (2023) taxonomic update of RNA-directed RNA polymerase-encoding negative-sense RNA viruses (realm Riboviria: kingdom Orthornavirae: phylum Negarnaviricota)". The Journal of General Virology. 104 (8): 001864. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.001864. PMC 10721048. PMID 37622664.

- ^ Conceicao, Carina; Bailey, Dalan (1 January 2021), "Animal Morbilliviruses (Paramyxoviridae)", in Bamford, Dennis H.; Zuckerman, Mark (eds.), Encyclopedia of Virology (Fourth Edition), Oxford: Academic Press, pp. 68–78, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-809633-8.20938-2, ISBN 978-0-12-814516-6, S2CID 242980358, retrieved 7 January 2024

- ^ Libbey, Jane E.; Fujinami, Robert S. (1 July 2023). "Morbillivirus: A highly adaptable viral genus". Heliyon. 9 (7): e18095. Bibcode:2023Heliy...918095L. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18095. ISSN 2405-8440. PMC 10362132. PMID 37483821.

- ^ Haas, L.; Barrett, T. (12 January 1996). "Rinderpest and Other Animal Morbillivirus Infections: Comparative Aspects and Recent Developments". Journal of Veterinary Medicine, Series B. 43 (1–10): 411–420. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0450.1996.tb00333.x. PMID 8885706.

- ^ De Vries, Rory D.; Duprex, W. Paul; De Swart, Rik L. (3 February 2015). "Morbillivirus Infections: An Introduction". Viruses. 7 (2): 699–706. doi:10.3390/v7020699. ISSN 1999-4915. PMC 4353911. PMID 25685949.

- ^ Barrett, Thomas; Banyard, Ashley C.; Diallo, Adama (1 January 2006), Barrett, Thomas; Pastoret, Paul-Pierre; Taylor, William P. (eds.), "3 - Molecular biology of the morbilliviruses", Rinderpest and Peste des Petits Ruminants, Biology of Animal Infections, Oxford: Academic Press, pp. 31–IV, doi:10.1016/b978-012088385-1/50033-2, ISBN 978-0-12-088385-1, retrieved 7 January 2024

- ^ Barrett, T.; Rossiter, P. B. (1 January 1999), Margniorosch, Karl; Murphy, Frederick A.; Shatkin, Aaron J. (eds.), Rinderpest: The Disease and Its Impact on Humans and Animals, Advances in Virus Research, vol. 53, Academic Press, pp. 89–110, doi:10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60344-9, ISBN 978-0-12-039853-9, PMID 10582096