UGM-27 Polaris

| UGM-27 Polaris | |

|---|---|

Polaris A-3 on launch pad before a test firing at Cape Canaveral | |

| Type | Submarine-launched ballistic missile |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1961–1996 |

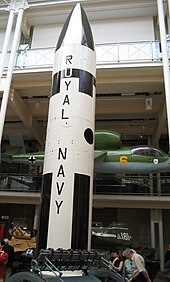

| Used by | United States Navy, Royal Navy |

| Production history | |

| Designed | 1956–1960 |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Corporation |

| Variants | A-1, A-2, A-3, Chevaline |

| Specifications (Polaris A-3 (UGM-27C)) | |

| Mass | 35,700 lb (16,200 kg) |

| Height | 32 ft 4 in (9.86 m) |

| Diameter | 4 ft 6 in (1,370 mm) |

| Warhead | 1 x W47, 3 × W58 thermonuclear weapon |

| Blast yield | 3 × 200 kt |

| Engine | First stage, Aerojet General Solid-fuel rocket Second stage, Hercules rocket |

| Propellant | Solid propellant |

Operational range | 2,500 nautical miles (4,600 km) |

| Maximum speed | 8,000 mph (13,000 km/h) |

Guidance system | Inertial |

Steering system | Thrust vectoring |

| Accuracy | CEP 3,000 feet (910 m) |

Launch platform | Ballistic missile submarines |

The UGM-27 Polaris missile was a two-stage solid-fueled nuclear-armed submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM). As the United States Navy's first SLBM, it served from 1961 to 1980.

In the mid-1950s the Navy was involved in the Jupiter missile project with the U.S. Army, and had influenced the design by making it squat so it would fit in submarines. However, they had concerns about the use of liquid fuel rockets on board ships, and some consideration was given to a solid fuel version, Jupiter S. In 1956, during an anti-submarine study known as Project Nobska, Edward Teller suggested that very small hydrogen bomb warheads were possible. A crash program to develop a missile suitable for carrying such warheads began as Polaris, launching its first shot less than four years later, in February 1960.[1]

As the Polaris missile was fired underwater from a moving platform, it was essentially invulnerable to counterattack. This led the Navy to suggest, starting around 1959, that they be given the entire nuclear deterrent role. This led to new infighting between the Navy and the U.S. Air Force, the latter responding by developing the counterforce concept that argued for the strategic bomber and ICBM as key elements in flexible response. Polaris formed the backbone of the U.S. Navy's nuclear force aboard a number of custom-designed submarines. In 1963, the Polaris Sales Agreement led to the Royal Navy taking over the United Kingdom's nuclear role, and while some tests were carried out by the Italian Navy, this did not lead to use.

The Polaris missile was gradually replaced on 31 of the 41 original SSBNs in the U.S. Navy by the MIRV-capable Poseidon missile beginning in 1972. During the 1980s, these missiles were replaced on 12 of these submarines by the Trident I missile. The 10 George Washington- and Ethan Allen-class SSBNs retained Polaris A-3 until 1980 because their missile tubes were not large enough to accommodate Poseidon. With USS Ohio beginning sea trials in 1980, these submarines were disarmed and redesignated as attack submarines to avoid exceeding the SALT II strategic arms treaty limits.

The Polaris missile program's complexity led to the development of new project management techniques, including the Program Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT) to replace the simpler Gantt chart methodology.

History and development

[edit]The Polaris missile replaced an earlier plan to create a submarine-based missile force based on a derivative of the U.S. Army Jupiter Intermediate-range ballistic missile. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke appointed Rear Admiral W. F. "Red" Raborn as head of a Special Project Office to develop Jupiter for the Navy in late 1955. The Jupiter missile's large diameter was a product of the need to keep the length short enough to fit in a reasonably-sized submarine. At the seminal Project Nobska conference in 1956, with Admiral Burke present, nuclear physicist Edward Teller stated that a physically small one-megaton warhead could be produced for Polaris within a few years, and this prompted Burke to leave the Jupiter program and concentrate on Polaris in December of that year.[2][3] Polaris was spearheaded by the Special Project Office's Missile Branch under Rear Admiral Roderick Osgood Middleton,[4] and is still under the Special Project Office.[5] Admiral Burke later was instrumental in determining the size of the Polaris submarine force, suggesting that 40–45 submarines with 16 missiles each would be sufficient.[6] Eventually, the number of Polaris submarines was fixed at 41.[7]

The USS George Washington was the first submarine capable of deploying U.S. developed submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM). The responsibility of the development of SLBMs was given to the Navy and the Army. The Air Force was charged with developing a land-based intermediate range ballistic missile (IRBM), while an IRBM which could be launched by land or by sea was tasked to the Navy and Army.[8] The Navy Special Projects (SP) office was at the head of the project. It was led by Rear Admiral William Raborn.[8]

On September 13, 1955, James R. Killian, head of a special committee organized by President Eisenhower, recommended that both the Army and Navy come together under a program aimed at developing an intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM). The missile, later known as Jupiter, would be developed under the Joint Army-Navy Ballistic Missile Committee approved by Secretary of Defense Charles E. Wilson in early November of that year.[9] The first IRBM boasted a liquid-fueled design. Liquid fuel is compatible with aircraft; it was considered less compatible with submarines in the West, even though in the Soviet Navy liquid-fuelled SLBMs, none of which used cryogenic components, were in overwhelming majority, and R-29RMU2 is still in service with the Russian Navy As of 2021[update] (it's expected to be phased out after 2030). Solid fuels, on the other hand, make logistics and storage simpler and are safer.[8] Not only was the Jupiter a liquid fuel design, it was also very large; even after it was designed for solid fuel, it was still a whopping 160,000 pounds.[10] A smaller, new design would weigh much less, estimated at 30,000 pounds. The Navy would rather develop a smaller, more easily manipulated design. Edward Teller was one of the scientists encouraging the progress of smaller rockets. He argued that the technology needed to be discovered, rather than apply technology that is already created.[8] Raborn was also convinced he could develop smaller rockets. He sent officers to make independent estimates of size to determine the plausibility of a small missile; while none of the officers could agree on a size, their findings were encouraging nonetheless.[8]

Project Nobska

[edit]The U.S. Navy began work on nuclear-powered submarines in 1946. They launched the first one, the USS Nautilus in 1955. Nuclear powered submarines were the least vulnerable to a first strike from the Soviet Union. The next question that led to further development was what kind of arms the nuclear-powered submarines should be equipped with.[11] In the summer of 1956, the navy sponsored a study by the National Academy of Sciences on anti-submarine warfare at Nobska Point in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, known as Project NOBSKA. The navy's intention was to have a new missile developed that would be lighter than existing missiles and cover a range up to fifteen hundred miles. A problem that needed to be solved was that this design would not be able to carry the desired one-megaton thermonuclear warhead.

This study brought Edward Teller from the recently formed nuclear weapons laboratory at Livermore and J. Carson Mark, representing the Los Alamos nuclear weapons laboratory. Teller was already known as a nuclear salesman, but this became the first instance where there was a big betting battle where he outbid his Los Alamos counterpart. The two knew each other well: Mark was named head of the theoretical division of Los Alamos in 1947, a job that was originally offered for Teller. Mark was a cautious physicist and no match for Teller in a bidding war.[12]

At the NOBSKA summer study, Edward Teller made his famous contribution to the FBM program. Teller offered to develop a lightweight warhead of one-megaton strength within five years. He suggested that nuclear-armed torpedoes could be substituted for conventional ones to provide a new anti-submarine weapon. Livermore received the project. When Teller returned to Livermore, people were astonished by the boldness of Teller's promise. It seemed inconceivable with the current size of nuclear warheads, and Teller was challenged to support his assertion. He pointed out the trend in warhead technology, which indicated reduced weight to yield ratios in each succeeding generation.[13] When Teller was questioned about the application of this to the FBM program, he asked, ‘Why use a 1958 warhead in a 1965 weapon system?’[14]

Mark disagreed with Teller's prediction that the desired one-megaton warhead could be made to fit the missile envelope within the timescale envisioned. Instead, Mark suggested that half a megaton would be more realistic and he quoted a higher price and a longer deadline. This simply confirmed the validity of Teller's prediction in the Navy's eyes. Whether the warhead was half or one megaton mattered little so long as it fitted the missile and would be ready by the deadline.[13] Almost four decades later, Teller said, referring to Mark's performance, that it was “an occasion when I was happy about the other person being bashful.”[13] When the Atomic Energy Commission backed up Teller's estimate in early September, Admiral Burke and the Navy Secretariat decided to support SPO in heavily pushing for the new missile, now named Polaris by Admiral Raborn.

There is a contention that the Navy's "Jupiter" missile program was unrelated to the Army program. The Navy also expressed an interest in Jupiter as an SLBM, but left the collaboration to work on their Polaris. At first, the newly assembled SPO team had the problem of making the large, liquid-fuel Jupiter IRBM work properly. Jupiter retained the short, squat shape intended to fit in naval submarines. Its sheer size and volatility of its fuel made it very unsuited to submarine launching and was only slightly more attractive for deployment on ships. The missile continued to be developed by the Army's German team in collaboration with their main contractor, Chrysler Corporation. SPO's responsibility was to develop a sea-launching platform with necessary fire control and stabilization systems for that very purpose. The original schedule was to have a ship-based IRBM system ready for operation evaluation by January 1, 1960, and a submarine-based one by January 1, 1965.[15] However, the Navy was deeply dissatisfied with the liquid fuel IRBM. The first concern was that the cryogenic liquid fuel was not only extremely dangerous to handle, but launch-preparations were also very time-consuming. Second, an argument was made that liquid-fueled rockets gave relatively low initial acceleration, which is disadvantageous in launching a missile from a moving platform in certain sea states. By mid-July 1956, the Secretary of Defense's Scientific Advisory Committee had recommended that a solid-propellant missile program be fully instigated but not using the unsuitable Jupiter payload and guidance system. By October 1956, a study group comprising key figures from Navy, industry and academic organizations considered various design parameters of the Polaris system and trade-offs between different sub-sections. The estimate that a 30,000-pound missile could deliver a suitable warhead over 1500 nautical miles was endorsed. With this optimistic assessment, the Navy now decided to scrap the Jupiter program altogether and sought out the Department of Defense to back a separate Navy missile.[16] A huge surfaced submarine would carry four "Jupiter" missiles, which would be carried and launched horizontally.[17] This was probably the never-built SSM-N-2 Triton program.[18] However, a history of the Army's Jupiter program states that the Navy was involved in the Army program, but withdrew at an early stage.[5]

Originally, the Navy favored cruise missile systems in a strategic role, such as the Regulus missile deployed on the earlier USS Grayback and a few other submarines, but a major drawback of these early cruise missile launch systems (and the Jupiter proposals) was the need to surface, and remain surfaced for some time, to launch. Submarines were very vulnerable to attack during launch, and a fully or partially fueled missile on deck was a serious hazard. The difficulty of preparing a launch in rough weather was another major drawback for these designs, but rough sea conditions did not unduly affect Polaris' submerged launches.

It quickly became apparent that solid-fueled ballistic missiles had advantages over cruise missiles in range and accuracy, and could be launched from a submerged submarine, improving submarine survivability.

The prime contractor for all three versions of Polaris was Lockheed Missiles and Space Company (now Lockheed Martin).

The Polaris program started development in 1956. USS George Washington, the first U.S. missile submarine, successfully launched the first Polaris missile from a submerged submarine on July 20, 1960. The A-2 version of the Polaris missile was essentially an upgraded A-1, and it entered service in late 1961. It was fitted on a total of 13 submarines and served until June 1974. Ongoing problems with the W-47 warhead, especially with its mechanical arming and safing equipment, led to large numbers of the missiles being recalled for modifications, and the U.S. Navy sought a replacement with either a larger yield or equivalent destructive power. The result was the W-58 warhead used in a "cluster" of three warheads for the Polaris A-3, the final model of the Polaris missile.

One of the initial problems the Navy faced in creating an SLBM was that the sea moves, while a launch platform on land does not. Waves and swells rocking the boat or submarine, as well as possible flexing of the ship's hull, had to be taken into account to properly aim the missile.

The Polaris development was kept on a tight schedule and the only influence that changed this was the USSR's launching of Sputnik on October 4, 1957.[8] This caused many working on the project to want to accelerate development. The launch of a second Russian satellite and pressing public and government opinions caused Secretary Wilson to move the project along more quickly.[8]

The Navy favored an underwater launch of an IRBM, although the project began with an above-water launch goal. They decided to continue the development of an underwater launch, and developed two ideas for this launch: wet and dry. Dry launch meant encasing the missile in a shell that would peel away when the missile reached the water's surface.[8] Wet launch meant shooting the missile through the water without a casing.[8] While the Navy was in favor of a wet launch, they developed both methods as a failsafe.[8] They did this with the development of gas and air propulsion of the missile out of the submerged tube as well.

The first Polaris missile tests[8] were given the names “AX-#” and later renamed “A1X-#”. Testing of the missiles occurred:

- September 24, 1958: AX-1, at Cape Canaveral from a launch pad; the missile was destroyed, after it failed to turn into the correct trajectory following a programming-error.

- October 1958: AX-2, at Cape Canaveral from a launch pad; exploded on the launch pad.

- December 30, 1958: AX-3, at Cape Canaveral from a launch pad; launched correctly, but was destroyed because of the fuel overheating.

- January 19, 1959: AX-4, at Cape Canaveral from launch pad: launched correctly but began to behave erratically and was destroyed.

- February 27, 1959: AX-5, at Cape Canaveral from launch pad: launched correctly but began to behave erratically and was destroyed.

- April 20, 1959: AX-6, at Cape Canaveral from launch pad: this test was a success. The missile launched, separated, and splashed into the Atlantic 300 miles off shore.

It was in between these two tests that the inertial guidance system was developed and implemented for testing.

- July 1, 1959: AX-11 at Cape Canaveral from a launch pad: this launch was successful, but pieces of the missile detached causing failure. It did show that the new guidance systems worked.

Guidance

[edit]At the time that the Polaris project went live, submarine navigation systems accuracy was adequate for existing weapons systems. Initially, developers of Polaris were set to utilize the existing 'Stable Platform' configuration of the inertial guidance system. Created at the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, this Ships Inertial Navigation System (SINS) was supplied to the Navy in 1954.[10] The developers of Polaris encountered many issues from the outset of the project, including the outdated technology of the gyroscopes they would be implementing.

This 'Stable Platform' configuration did not account for the change in gravitational fields that the submarine would experience while it was in motion, nor did it account for the ever-altering position of the Earth. This problem raised many concerns, as this would make it nearly impossible for navigational readouts to remain accurate and reliable. A submarine equipped with ballistic missiles was of little to no use if operators had no way to direct them. The Polaris developers then turned to a guidance system that had been abandoned by the U.S. Air Force, the XN6 Autonavigator. Developed by the Autonetics Division of North American Aviation for the U.S. Air Force Navaho, the XN6 was a system designed for air-breathing cruise missiles, but by 1958 had proved useful for installment on submarines.[10]

A predecessor to the GPS satellite navigation system, the Transit system (later called NAVSAT), was developed because the submarines needed to know their position at launch in order for the missiles to hit their targets. Two American physicists at Johns Hopkins's Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), William Guier and George Weiffenbach, began this work in 1958. A computer small enough to fit through a submarine hatch was developed in 1958, the AN/UYK-1. It was used to interpret the Transit satellite data and send guidance information to the Polaris, which had its own guidance computer made with ultra miniaturized electronics, very advanced for its time, because there wasn't much room in a Polaris—there were 16 on each submarine. The Ship's Inertial Navigation System (SINS) was developed earlier to provide a continuous dead reckoning update of the submarine's position between position fixes via other methods, such as LORAN. This was especially important in the first few years of Polaris, because Transit was not operational until 1964.[19] By 1965 microchips similar to the Texas Instruments units made for the Minuteman II were being purchased by the Navy for the Polaris. The Minuteman guidance systems each required 2000 of these, so the Polaris guidance system may have used a similar number. To keep the price under control, the design was standardized and shared with Westinghouse Electric Company and RCA. In 1962, the price for each Minuteman chip was $50. The price dropped to $2 in 1968.[20]

Polaris A-3

[edit]

This missile replaced the earlier A-1 and A-2 models in the U.S. Navy, and also equipped the British Polaris force. The A-3 had a range extended to 2,500 nautical miles (4,600 kilometres) and a new weapon bay housing three Mk 2 re-entry vehicles (ReB or Re-Entry Body in U.S. Navy and British usage); and the new W-58 warhead of 200 kt yield. This arrangement was originally described as a "cluster warhead" but was replaced with the term Multiple Re-Entry Vehicle (MRV). The three warheads, also known as "bomblets", were spread out in a "shotgun" like pattern above a single target and were not independently targetable (such as a MIRV missile is). The three warheads were stated to be equivalent in destructive power to a single one-megaton warhead due to their spread out pattern on the target. The first Polaris submarine outfitted with MRV A-3's was the USS Daniel Webster in 1964.[21] Later the Polaris A-3 missiles (but not the ReBs) were also given limited hardening to protect the missile electronics against nuclear electromagnetic pulse effects while in the boost phase. This was known as the A-3T ("Topsy") and was the final production model.

Polaris A-1

[edit]

The initial test model of the Polaris was referred to as the AX series and made its maiden flight from Cape Canaveral on September 24, 1958. The missile failed to perform its pitch and roll maneuver and instead just flew straight up, however the flight was considered a partial success (at that time, "partial success" was used for any missile test that returned usable data). The next flight on October 15 failed spectacularly when the second stage ignited on the pad and took off by itself. Range Safety blew up the errant rocket while the first stage sat on the pad and burned. The third and fourth tests (December 30 and January 9) had problems due to overheating in the boattail section. This necessitated adding extra shielding and insulation to wiring and other components. When the final AX flight was conducted a year after the program began, 17 Polaris missiles had been flown of which five met all of their test objectives.

The first operational version, the Polaris A-1, had a range of 1,400 nautical miles (2,600 kilometres) and a single Mk 1 re-entry vehicle, carrying a single W-47-Y1 600 kt nuclear warhead, with an inertial guidance system which provided a circular error probable (CEP) of 1,800 meters (5,900 feet). The two-stage solid propellant missile had a length of 28.5 ft (8.7 m), a body diameter of 54 inches (1.4 m), and a launch weight of 28,800 pounds (13,100 kg).[22]

USS George Washington was the first fleet ballistic missile submarine (SSBN in U.S. naval terminology) and she and all other Polaris submarines carried 16 missiles. Forty more SSBNs were launched in 1960 to 1966.

Work on its W47 nuclear warhead began in 1957 at the facility that is now called the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory by a team headed by John Foster and Harold Brown.[23] The Navy accepted delivery of the first 16 warheads in July 1960. On May 6, 1962, a Polaris A-2 missile with a live W47 warhead was tested in the "Frigate Bird" test of Operation Dominic by USS Ethan Allen in the central Pacific Ocean, the only American test of a live strategic nuclear missile.

The two stages were both steered by thrust vectoring. Inertial navigation guided the missile to about a 900 m (3,000-foot) CEP, insufficient for use against hardened targets. They were mostly useful for attacking dispersed military surface targets (airfields or radar sites), clearing a pathway for heavy bombers, although in the general public perception Polaris was a strategic second-strike retaliatory weapon.[citation needed]

After Polaris

[edit]To meet the need for greater accuracy over the longer ranges the Lockheed designers included a reentry vehicle concept, improved guidance, fire control, and navigation systems to achieve their goals. To obtain the major gains in performance of the Polaris A3 in comparison to early models, there were many improvements, including propellants and material used in the construction of the burn chambers. The later versions (the A-2, A-3, and B-3) were larger, weighed more, and had longer ranges than the A-1. The range increase was most important: The A-2 range was 1,500 nautical miles (2,800 kilometres), the A-3 2,500 nautical miles (4,600 kilometres), and the B-3 2,000 nautical miles (3,700 kilometres). The A-3 featured multiple re-entry vehicles (MRVs) which spread the warheads about a common target, and the B-3 was to have penetration aids to counter Soviet Anti-Ballistic Missile defenses.

The U.S. Navy began to replace Polaris with Poseidon in 1972. The B-3 missile evolved into the C-3 Poseidon missile, which abandoned the decoy concept in favor of using the C3's greater throw-weight for larger numbers (10–14) of new hardened high-re-entry-speed reentry vehicles that could overwhelm Soviet defenses by sheer weight of numbers, and its high speed after re-entry. This turned out to be a less than reliable system and soon after both systems were replaced by the Trident. A proposed Undersea Long-Range Missile System (ULMS) program outlined a long-term plan which proposed the development of a longer-range missile designated as ULMS II, which was to achieve twice the range of the existing Poseidon (ULMS I) missile. In addition to a longer-range missile, a larger submarine (Ohio-class) was proposed to replace the submarines currently being used with Poseidon. The ULMS II missile system was designed to be retrofitted to the existing SSBNs, while also being fitted to the proposed Ohio-class submarine.

In May 1972, the term ULMS II was replaced with Trident. The Trident was to be a larger, higher-performance missile with a range capacity greater than 6000 miles. Under the agreement, the United Kingdom paid an additional 5% of their total procurement cost of 2.5 billion dollars to the U.S. government as a research and development contribution.[24] In 2002, the United States Navy announced plans to extend the life of the submarines and the D5 missiles to the year 2040. This requires a D5 Life Extension Program (D5LEP), which is currently underway. The main aim is to replace obsolete components at minimal cost by using commercial off the shelf (COTS) hardware; all the while maintaining the demonstrated performance of the existing Trident II missiles.[25]

STARS

[edit]

STARS, the Strategic Target System program, is a BMDO program managed by the U. S. Army Space and Strategic Defense Command (SSDC). It began in 1985 in response to concerns that the supply of surplus Minuteman I boosters used to launch targets and other experiments on intercontinental ballistic missile flight trajectories in support of the Strategic Defense Initiative would be depleted by 1988. SSDC tasked Sandia National Laboratories, a Department of Energy laboratory, to develop an alternative launch vehicle using surplus Polaris boosters. The Sandia National Laboratories developed two STARS booster configurations: STARS I and STARS II.

STARS I consisted of refurbished Polaris first and second stages and a commercially procured Orbis I third stage. It can deploy single or multiple payloads, but the multiple payloads cannot be deployed in a manner that simulates the operation of a post-boost vehicle. To meet this specific need, Sandia developed an Operations and Deployment Experiments Simulator (ODES), which functions as a PBV. When ODES was added to STARS I, the configuration became known as STARS II. The development phase of the STARS program was completed in 1994, and BMDO provided about $192.1 million for this effort. The operational phase began in 1995. The first STARS I flight, a hardware check-out flight, was launched in February 1993, and the second flight, a STARS I reentry vehicle experiment, was launched in August 1993.

The third flight, a STARS II development mission, was launched in July 1994, with all three flights considered to be successful by BMDO. The Secretary of Defense conducted a comprehensive review in 1993 of the nation's defense strategy, which drastically reduced the number of STARS launches required to support National Missile Defense (NMD)2 and BMDO funding. Due to the launch and budget reductions, the STARS office developed a draft long-range plan for the STARS program. The study examined three options:

- Place the program in a dormant status, but retain the capability to reactivate it.

- Terminate the program.

- Continue the program.

When the STARS program was started in 1985 it was perceived that there would be four launches per year. Because of the large number of anticipated launches and an unknown defect rate for surplus Polaris motors, the STARS office acquired 117 first-stage and 102 second-stage surplus motors. As of December 1994, seven first-stage and five second-stage refurbished motors were available for future launches. BMDO is currently evaluating STARS as a potential long-range system for launching targets for development tests of future Theater Missile Defense 3 systems. STARS I was first launched in 1993, and from 2004 onwards has served as the standard booster for trials of the Ground-Based Interceptor.[26]

British Polaris

[edit]

From the early days of the Polaris program, American senators and naval officers suggested that the United Kingdom might use Polaris. In 1957 Chief of Naval Operations Arleigh Burke and First Sea Lord Louis Mountbatten began corresponding on the project. After the cancellations of the Blue Streak and Skybolt missiles in the 1960s, under the 1962 Nassau Agreement that emerged from meetings between Harold Macmillan and John F. Kennedy, the United States would supply Britain with Polaris missiles, launch tubes, ReBs, and the fire-control systems. Britain would make its own warheads and initially proposed to build five ballistic missile submarines, later reduced to four by the incoming Labour government of Harold Wilson, with 16 missiles to be carried on each boat. The Nassau Agreement also featured very specific wording. The intention of wording the agreement in this manner was to make it intentionally opaque. The sale of the Polaris was malleable in how an individual country could interpret it due to the diction choices taken in the Nassau Agreement. For the United States of America, the wording allowed for the sale to fall under the scope of NATO's deterrence powers. On the other hand, for the British, the sale could be viewed as a solely British deterrent.[27] The Polaris Sales Agreement was signed on April 6, 1963.[28]

In return, the British agreed to assign control over their Polaris missile targeting to the SACEUR (Supreme Allied Commander, Europe), with the provision that in a national emergency when unsupported by the NATO allies, the targeting, permission to fire, and firing of those Polaris missiles would reside with the British national authorities. Nevertheless, the consent of the British Prime Minister is and has always been required for the use of British nuclear weapons, including SLBMs.

The operational control of the Polaris submarines was assigned to another NATO Supreme Commander, the SACLANT (Supreme Allied Commander, Atlantic), who is based near Norfolk, Virginia, although the SACLANT routinely delegated control of the missiles to his deputy commander in the Eastern Atlantic area, COMEASTLANT, who was always a British admiral.

Polaris was the largest project in the Royal Navy's peacetime history. Although in 1964 the new Labour government considered cancelling Polaris and turning the submarines into conventionally armed hunter-killers, it continued the program as Polaris gave Britain a global nuclear capacity—perhaps east of Suez—at a cost £150 million less than that of the V bomber force. By adopting many established, American, methodologies and components Polaris was finished on time and within budget. On 15 February 1968, HMS Resolution, the lead ship of her class, became the first British vessel to fire a Polaris.[28] All Royal Navy SSBNs have been based at Faslane, only a few miles from Holy Loch. Although one submarine of the four was always in a shipyard undergoing a refit, recent declassifications of archived files disclose that the Royal Navy deployed four boatloads of reentry vehicles and warheads, plus spare warheads for the Polaris A3T, retaining a limited ability to re-arm and put to sea the submarine that was in refit. When replaced by the Chevaline warhead, the sum total of deployed RVs and warheads was reduced to three boatloads.

Chevaline

[edit]

The original U.S. Navy Polaris had not been designed to penetrate anti-ballistic missile (ABM) defenses, but the Royal Navy had to ensure that its small Polaris force operating alone, and often with only one submarine on deterrent patrol, could penetrate the ABM screen around Moscow. Britain's submarines featured the Polaris A3T missiles, a modification to the model of the Polaris used by the U.S. from 1968 to 1972. Similar concerns were present in the U.S. as well, resulting in a new American defense program.[29]

The program became known as Antelope, and its purpose was to alter the Polaris. Various aspects of the Polaris, such as increasing deployment efficiency and creating ways to improve the penetrative power were specific items considered in the tests conducted during the Antelope program. The British's uncertainty with their missiles led to the examination of the Antelope program. The assessments of Antelope occurred at Aldermaston. Evidence from the evaluation of Antelope led to the British decision to undertake their program following that of the United States.[27]

The result was a programme called Chevaline that added multiple decoys, chaff, and other defensive countermeasures. Its existence was only revealed in 1980, partly because of the cost overruns of the project, which had almost quadrupled the original estimate given when the project was finally approved in January 1975. The program also ran into trouble when dealing with the British Labour Party. Their Chief Scientific Adviser, Solly Zuckerman, believed that Britain no longer needed new designs for nuclear weapons and no more nuclear warhead tests would be necessary. Though the Labour Party provided a clear platform on nuclear weapons, the Chevaline program found supporters. One such individual who supported modification to the Polaris was the Secretary of State for Defence, Denis Healey.[27]

Despite the approval of the program, the expenses caused hurdles that augmented the time it took for the system to come to fruition. The cost of the project led to Britain's disbanding the program in 1977. The system became operational in mid-1982 on HMS Renown, and the last British SSBN submarine was equipped with it in mid-1987.[30] Chevaline was withdrawn from service in 1996.

Though Britain adopted the Antelope program methods, no input on the design came from the United States. Aldermaston was solely responsible for the Chevaline warheads.

Replacement

[edit]The British did not ask to extend the Polaris Sales Agreement to cover the Polaris successor Poseidon due to its cost.[28] The Ministry of Defence upgraded its nuclear missiles to the longer-ranged Trident after much political wrangling within the Callaghan Labour Party government over its cost and whether it was necessary. The outgoing Prime Minister James Callaghan made his government's papers on Trident available to Margaret Thatcher's new incoming Conservative Party government, which took the decision to acquire the Trident C4 missile.

A subsequent decision to upgrade the missile purchase to the even larger, longer-ranged Trident D5 missile was possibly taken to ensure that there was missile commonality between the U.S. Navy and the Royal Navy, which was considerably important when the Royal Navy Trident submarines were also to use the Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay.

Even though the U.S. Navy initially deployed the Trident C4 missile in the original set of its Ohio-class submarines, it was always planned to upgrade all of these submarines to the larger and longer-ranged Trident D5 missile—and that eventually, all of the C4 missiles would be eliminated from the U.S. Navy. This change-over has been completely carried out, and no Trident C4 missiles remain in service.

The Polaris missile remained in Royal Navy service long after it had been completely retired and scrapped by the U.S. Navy in 1980–1981. Consequently, many spare parts and repair facilities for the Polaris that were located in the U.S. ceased to be available (such as at Lockheed, which had moved on first to the Poseidon and then to the Trident missile).

Italy

[edit]During its reconstruction program in 1957–1961, the Italian cruiser Giuseppe Garibaldi was fitted with four Polaris missile launchers located in the aft part of the ship. The Italian usage of Polaris missiles was partially the result of the Kennedy administration. Prior to 1961, Italy and Turkey were equipped with Jupiter missiles. Three factors were instrumental in the movement away from the Jupiter project in Italy and Turkey: the president's view of the project, new understanding about weapons systems and the diminished necessity of the Jupiter missile. The Joint Congressional Committee report on Atomic Energy accentuated the three previous factors in Italy's decision to switch to the Polaris missiles.[31]

Successful tests held in 1961–1962 induced the United States to study a NATO Multilateral Nuclear Force (MLF), consisting of 25 international surface vessels from the US, United Kingdom, France, Italy, and West Germany, equipped with 200 Polaris nuclear missiles,[32] enabling European allies to participate in the management of the NATO nuclear deterrent.[31]

The report advocated a change from the outdated Jupiter missiles, already housed by the Italians, to the newer missile, Polaris. The report resulted in Secretary of State Dean Rusk and assistant Secretary of Defense Paul Nitze discussing the possibility of changing the warheads in the Mediterranean. The Italians were not swayed by the American's interest in modernizing their warheads. However, after the Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy met the Italian leader Amintore Fanfani in Washington. Fanfani conceded and went along with Kennedy's Polaris plan, despite the Italians hoping to stick with the Jupiter missile.[31]

The MLF plan, as well as the Italian Polaris Program, were abandoned, both for political reasons (in consequence of the Cuban Missile Crisis) and the initial operational availability of the first SSBN George Washington, which was capable of launching SLBMs while submerged, a solution preferable to surface-launched missiles.

Italy developed a new domestic version of the missile, the SLBM-designated Alfa.[33] That program was cancelled in 1975 after Italy ratified the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, with the final launch of the third prototype in 1976.

Two Italian Navy Andrea Doria-class cruisers, commissioned in 1963–1964, were "fitted for but not with" two Polaris missile launchers per ship. All four launchers were built but never installed, and were stored at the La Spezia naval facility.

The Italian cruiser Vittorio Veneto, launched in 1969, was also "fitted for but not with" four Polaris missile launchers. During refit periods in 1980–1983, these facilities were removed and used for other weapons and systems.

Operators

[edit]

- Marina Militare (tests only, never fully operational)

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ "Polaris A1". Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Teller, Edward (2001). Memoirs: A Twentieth Century Journey in Science and Politics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Perseus Publishing. pp. 420–421. ISBN 978-0-7382-0532-8.

- ^ Friedman, pp. 109–114.

- ^ "Navy Office of Information biography on Roderick Osgood Middleton". Archived from the original on 15 July 2007.

- ^ a b "History of the Jupiter Missile". pp. 23–35.

- ^ "How Much is Enough?": The U.S. Navy and "Finite Deterrence", National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 275

- ^ Friedman, pp. 196–197.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Miles, Wyndham D. (1963). "The Polaris". Technology and Culture. 4 (4): 478–489. doi:10.2307/3101381. JSTOR 3101381. S2CID 260095128.

- ^ von Braun, Wernher; I. Ordway III, Frederick (1969). History of Rocketry and Space Travel. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company. pp. 128–133.

- ^ a b c MacKenzie, Donald; Spinardi, Graham (August 1988). "The Shaping of Nuclear Weapon System Technology: US Fleet Ballistic Missile Guidance and Navigation: I: From Polaris to Poseidon". Social Studies of Science. 18 (3): 419–463. doi:10.1177/030631288018003002. S2CID 108709165.

- ^ Istvan Hargittai. p. 357. Judging Edward Teller: A Closer Look at One of the Most Influential Scientists of the Twentieth Century [ISBN missing]

- ^ Istvan Hargittai. p. 358. Judging Edward Teller: A Closer Look at One of the Most Influential Scientists of the Twentieth Century

- ^ a b c Graham Spinardi. p. 30. From Polaris to Trident: The Development of U.S. Fleet Ballistic Missile Technology [ISBN missing]

- ^ William F. Whitmore, Lockheed Missiles and Space Division (Whitemore 1961, p. 263)

- ^ Graham Spinardi. p. 27. From Polaris to Trident: The Development of US Fleet Ballistic Missile Technology [ISBN missing]

- ^ Graham Spinardi. p. 28. From Polaris to Trident: The Development of US Fleet Ballistic Missile Technology

- ^ 1946:1[dead link]

- ^ Friedman, p. 183

- ^ "Danchik, Robert J., "An Overview of Transit Development", pp. 18–26" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-21. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- ^ The Innovators: How a Group of Inventors, Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution. Simon & Schuster. 2014. pp. 181–182.

- ^ Polmar, Norman. (2009). The U.S. nuclear arsenal : a history of weapons and delivery systems since 1945. Norris, Robert S. (Robert Stan). Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1557506818. OCLC 262888426.

- ^ "Britannica Academic".

- ^ "Fifty Years of Innovation through Nuclear Weapon Design". Science & Technology Review: 5–6. January–February 2002. Archived from the original on 2008-11-15. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

Livermore designers, led by physicists Harold Brown and John Foster ... the assignment in 1957 of developing the warhead for the Navy's Polaris missile ...

- ^ Ministry of Defence and Property Services Agency: Control and Management of the Trident Programme. National Audit Office. 29 June 1987. Part 4. ISBN 978-0-10-202788-4.

- ^ "Navy Awards Lockheed Martin $248 Million Contract for Trident II D5 Missile Production and D5 Service Life Extension" (Press release). Lockheed Martin Space Systems Company. 29 January 2002. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ^ Parsch, Andreas (2007). "Sandia STARS". Directory of U.S. Military Rockets and Missiles Appendix 4: Undesignated Vehicles. Designation-Systems.net. Archived from the original on 2017-01-20. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- ^ a b c Spinardi, Graham (August 1997). "Aldermaston and British Nuclear Weapons Development: Testing the 'Zuckerman Thesis'". Social Studies of Science. 27 (4): 547–582. doi:10.1177/030631297027004001. JSTOR 285558. S2CID 108446840.

- ^ a b c Priest, Andrew (September 2005). "In American Hands: Britain, the United States and the Polaris Nuclear Project 1962–1968". Contemporary British History. 19 (3): 353–376. doi:10.1080/13619460500100450. S2CID 144941756.

- ^ Parr, Helen (May 2013). "The British Decision to Upgrade Polaris, 1970–4". Contemporary European History. 22 (2): 253–274. doi:10.1017/S0960777313000076. S2CID 163187309. ProQuest 1323206104.

- ^ History of the British Nuclear Arsenal, Nuclear Weapons Archive website

- ^ a b c Loeb, Larry M. (1976). "Jupiter Missiles in Europe: A Measure of Presidential Power". World Affairs. 139 (1): 27–39. JSTOR 20671652.

- ^ "NATO MLF". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ^ Italian Alfa Program Archived 2013-05-22 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- Friedman, Norman (1994). U.S. Submarines Since 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 978-1-55750-260-5.

- "Polaris: A Further Report on the Fleet Ballistic Missile System". Flight International: 751–757. 7 November 1963.

Further reading

[edit]- Parr, Helen. "The British Decision to Upgrade Polaris, 1970–4", Contemporary European History (2013) 22#2 pp. 253–274.

- Moore, R. "A Glossary of British Nuclear Weapons" Prospero/Journal of BROHP. 2004.

- Panton, Dr F. The Unveiling of Chevaline. Prospero/Journal of BROHP. 2004.

- Panton, Dr F. Polaris Improvements and the Chevaline System. Prospero/Journal of BROHP. 2004.

- Jones, Dr Peter, Director, AWE (Ret). Chevaline Technical Programme. Prospero. 2005.

- Various authors – The History of the UK Strategic Deterrent: The Chevaline Programme, Proceedings of a Guided Flight Group conference that took place on October 28, 2004, Royal Aeronautical Society. ISBN 1-85768-109-6.

- The National Archives, London. Various declassified public-domain documents.

- Hansen, Chuck (2007). Swords of Armageddon: U.S. Nuclear Weapons Development Since 1945 (PDF) (CD-ROM & download available) (2 ed.). Sunnyvale, California: Chukelea Publications. ISBN 978-0-9791915-0-3. 2,600 pages.

External links

[edit]- Lockheed Martin Polaris Website

- Federation of American Scientists history of A-1 Polaris; see also "a-2.htm," "a-3.htm," and "b-3.htm". (Now known to be an outdated source with many inaccuracies.)

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120314120957/http://www.mcis.soton.ac.uk/Site_Files/pdf/nuclear_history/glossary.pdf University of Southampton, 2005.

- Polaris launch at sea