Date rape drug

A date rape drug is any drug that incapacitates another person and renders that person vulnerable to sexual assault, including rape. The substances are associated with date rape because of reported incidents of their use in the context of two people dating, during which the victim is sexually assaulted or raped or suffers other harm. However, substances have also been exploited during retreats, for example ayahuasca retreats. The substances are not exclusively used to perpetrate sexual assault or rape, but are the properties or side-effects of substances normally used for legitimate medical purposes. One of the most common incapacitating agents for date rape is alcohol, administered either surreptitiously[1] or consumed voluntarily,[2] rendering the victim unable to make informed decisions or give consent.

Frequency

[edit]No comprehensive data exists on the frequency of drug-facilitated sexual assaults involving the use of surreptitious drug administration, due to the report rate of assaults and because rape victims who do report are often either never tested for these drugs, are tested for the wrong ones, or the tests are administered after the drug has been metabolized and left their body.[3]

A 1999 study of 1,179 urine specimens from victims of suspected drug-facilitated sexual assaults in 49 American states found six (0.5%) positive for Rohypnol, 97 (8%) positive for other benzodiazepines, 48 (4.1%) positive for GHB, 451 (38%) positive for alcohol and 468 (40%) negative for any of the drugs searched for.[4] A similar study of 2,003 urine samples of victims of suspected drug-facilitated sexual assaults found less than 2% tested positive for Rohypnol or GHB.[5] The samples used in these studies could only be verified as having been submitted within a 72-hour time frame or a 48-hour time frame.

A three-year study in the UK detected sedatives or disinhibiting drugs that victims said they had not voluntarily taken in the urine of two percent of suspected drug-facilitated sexual assault victims. In 65% of the 1,014 cases included in this study, testing could not be conducted within a time frame that would allow detection of GHB.[6] A 2009 Australian study found that of 97 instances of patients admitted to hospital believing their drinks might have been spiked, illicit drugs were detected in 28% of samples, and nine cases were identified as "plausible drink spiking cases". This study defined a "plausible drink spiking case" in such a way that cases where (a) patients believed that their drink had been spiked, and (b) lab tests showed agents that patients said they had not ingested would still be ruled out as plausible if the patient did not also (c) exhibit "signs and symptoms" that were considered "consistent with agents detected by laboratory screening."[7]

Documented routes of administration

[edit]Oral

[edit]In slang, a Mickey Finn (or simply a Mickey) is a drink laced with a psychoactive drug or incapacitating agent (especially chloral hydrate) given to someone without their knowledge, with intent to incapacitate them. Serving someone a "Mickey" is most commonly referred to as "slipping someone a mickey". Drink spiking is common practice by predators at drinking establishments who often lace alcoholic drinks with sedative drugs.[citation needed]

Syringe injection

[edit]Multiple reports of needle spiking were reported by young women in the United Kingdom from 2021 onwards.[8][9] On 27 October 2021, the Garda Síochána (Irish police) began an investigation after a woman was spiked with a needle in a Dublin nightclub.[10]

Documented date rape drugs

[edit]Depressants

[edit]Alcohol, consumed voluntarily, is the most commonly used drug involved in sexual assaults. Since the mid-1990s, the media and researchers have also documented an increased use of drugs such as flunitrazepam and ketamine to facilitate sexual assaults in the context of dating. [citation needed] Other drugs that have been used include hypnotics such as zopiclone, methaqualone, and the widely available zolpidem (Ambien); sedatives such as neuroleptics (anti-psychotics), chloral hydrate, and some histamine H1 antagonists; common recreational drugs such as ethanol, cocaine, and less common anticholinergics, barbiturates, opioids, PCP, scopolamine;[11] nasal spray ingredient oxymetazoline;[12][13][14] and certain GABAergics like GHB. Gamma-Butyrolactone is also often referred to as being used in sexual assaults.[15]

Alcohol

[edit]

Researchers agree that the drug most commonly involved in drug-facilitated sexual assaults is alcohol,[2] which the victim has consumed voluntarily in most cases.[citation needed] In most jurisdictions, alcohol is legal and readily available and is used in the majority of sexual assaults.[12] Many perpetrators use alcohol because their victims often drink it willingly, and can be encouraged to drink enough to lose inhibitions or consciousness. Sex with an unconscious victim is considered rape in most jurisdictions and some assailants have committed "rapes of convenience", assaulting a victim after he or she had become unconscious from drinking too much.[17]

Alcohol consumption is known to have effects on sexual behavior and aggression. During social interactions, alcohol consumption causes more biased appraisal of a partner's sexual motives while impairing communication about and enhancing misperception of sexual intentions, effects exacerbated by peer influence about how to behave when drinking.[18] The effects of alcohol at the point of forced sex commonly include an impaired ability to rectify misperceptions and a diminished ability to resist sexual advances and aggressive sexual behavior.[18]

The Blade released a special report, "The Making of an Epidemic," criticizing a study conducted in the 1990s that concluded that 55% of rape victims had been intoxicated. According to The Blade, the study specifically ignored an Ohio statute that excluded "situations where a person plies his intended partner with drink or drugs in hopes that lowered inhibition might lead to a liaison." The author of the study later admitted that the wording of the survey had been ambiguous.[19]

Alcohol in campus rape

[edit]The increase of sexual assaults on college campuses has been attributed to the social expectations of students to participate in alcohol consumption; social norm dictates that students drink heavily and engage in casual sex.[20]

Various studies have concluded the following:

- On average, at least 50% of college sexual assault cases are associated with alcohol use.[18]

- On college campuses, 74% of the perpetrators and 55% of the victims had been drinking alcohol.[18]

- In 2002, more than 70,000 students between the ages of 18 and 24 were victims of alcohol-related sexual assault in the U.S.[21][failed verification]

- In violent incidents recorded by the police in which alcohol was a factor, about 9% of the offenders and nearly 14% of the victims were under age 21.[21][failed verification]

Z-drugs

[edit]Zolpidem

[edit]Zolpidem (Ambien) is one of the most common date-rape drugs according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.[22] [dubious – discuss]

Benzodiazepines

[edit]Benzodiazepines (tranquilizers), such as Valium, Librium, Klonopin, Xanax, and Ativan, are prescribed to treat anxiety, panic attacks, insomnia, and several other conditions, and are also frequently used recreationally. Benzodiazepines are often used in drug-facilitated sexual assaults, with the most notorious being flunitrazepam (chemical name) or Rohypnol (proprietary or brand name), also known as "roofies," "rope," and "roaches."[23][24]

The benzodiazepines midazolam and temazepam were the two most common benzodiazepines utilized for date rape.[25]

Benzodiazepines can be detected in urine through the use of drug tests administered by medical officials or sold at pharmacies and performed at home. Most tests will detect benzodiazepines for a maximum of 72 hours after it was taken. Most general benzodiazepine detection tests will not detect Rohypnol: the drug requires a test specifically designed for that purpose. One new process can detect a 2 mg dose of Rohypnol for up to 28 days post-ingestion.[13][26] Other tests for Rohypnol include blood and hair tests. Because the most commonly used drug tests often yield false negatives for Rohypnol, experts recommend use of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis.[1][5][27]

Rohypnol

[edit]Rohypnol (Flunitrazepam) pills are typically small and dissolve readily into drinks without significantly affecting their taste or color, allowing the pills to be easily administered surreptitiously to victims.[28]

In one 2002 survey of 53 women who used Rohypnol recreationally, 10% said they were physically or sexually assaulted while under its influence.[5] If enough of the drug is taken, a person may experience a state of automatism or dissociation. After the drug wears off, users may find themselves unable to remember what happened while under its influence (anterograde amnesia), and feeling woozy, hung-over, confused, dizzy, sluggish and uncoordinated, often with an upset stomach. They may also have some difficulty moving their limbs normally.[1][5][27]

Rohypnol is believed to be commonly used in drug-facilitated sexual assaults in the United States, the United Kingdom, and throughout Europe, Asia and South America.[29] Although Rohypnol's use in drug-facilitated sexual assaults has been covered extensively in the news media, researchers disagree about how common such use actually is. Law enforcement manuals describe it as one of the drugs most commonly implicated in drug-facilitated sexual assaults.[1] Despite having a long half-life (18–28 hours) an incorrect belief is that Rohypnol is undetectable 12 hours after administration which may result in victims failing to get a blood or urine test the following day.

GHB

[edit]Gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) is a central nervous system depressant. It has no odor and tastes salty,[30] but the taste can be masked when mixed in a drink.[31]

GHB is used recreationally to stimulate euphoria, to increase sociability, to promote libido and lower inhibitions.[32] It is sold under names such as Rufies, Liquid E and Liquid X. It is usually taken orally, by the capful or teaspoon.[33]

From 1996 to 1999, 22 reports of GHB being used in drug-facilitated sexual assaults were made to the United States Drug Enforcement Administration. A 26-month study of 1,179 urine samples from suspected drug-facilitated sexual assaults across the United States found 4% positive for GHB.[32] The National Drug Intelligence Center (NDIC) says that in the United States GHB had surpassed Rohypnol as the substance most commonly used in drug-facilitated sexual assaults, likely because GHB is much more easily available, cheaper and leaves the body more quickly.[32][34] GHB is only detectable in urine for six to twelve hours after ingestion.[34]

Psychedelics

[edit]Ayahuasca

[edit]Ayahuasca has been used in some ayahuasca retreats to sexually abuse ayahuasca tourists.[35][36][37][38]

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)

[edit]MDMA is an empathogen. Although it is not sedating like other date rape drugs, it has been used to facilitate sexual assault.[39][40] It can increase disinhibition and sexual desire.[41] Often Ecstasy is combined with amphetamines or other drugs.

Detection

[edit]Several devices have, in recent years, been developed to detect the presence of date rape drugs, many designed with discreetness in mind. One, developed by two Tel Aviv University researchers, is a sensor for gamma-hydroxybutyric acid and ketamine, but appears similar to a straw, and sends a text to the user's phone to warn them.[42] In 2022, another "Smart Straw" product was designed by students at the University of Nantes: a non-electronic stainless steel straw including a ring that would change colors in the presence of GHB, Rohypnol, or ketamine.[43][44] Another, designed by four North Carolina State University students, is a nail polish that changes color in the presence of date rape drugs.[45] Several others have also been designed with these color-changing mechanisms in mind.[46][47]

Media coverage

[edit]There were three stories in the media about Rohypnol in 1993, 25 in 1994, and 854 in 1996.[citation needed] In early 1996, Newsweek magazine published "Roofies: The date-rape drug" which ended with the line "Don't take your eyes off your drink."[citation needed] That summer, researchers[who?] say[failed verification] all major American urban and regional newspapers covered date rape drugs, with headlines such as "Crackdown sought on date rape drug" (Los Angeles Times)[48] and "Drug zaps memory of rape victims" (San Francisco Chronicle).[49] In 1997 and 1998, the date rape drug story received extensive coverage on CNN, ABC's 20/20 and Primetime Live, as well as The Oprah Winfrey Show. Women were advised not to drink from punch bowls, not to leave a drink unattended and keeping drinks with them at all times (including when going to a dance or the bathroom, or using the phone), not to try new drinks, not to share drinks, not to drink anything with an unusual taste or appearance, take their own drinks to parties, drink nothing opened by another person, and if they feel sick to go with someone they know and not alone or with someone they just met or do not know.[citation needed]

News media has been criticized for overstating the threat of drug-facilitated sexual assault, for providing "how to" material for potential date rapists and for advocating "grossly excessive protective measures for women, particularly in coverage between 1996 and 1998.[50][51] Law enforcement representatives and feminists have also been criticized for supporting the overstatements for their own purposes.[52]

Craig Webber states that this extensive coverage has created or amplified a moral panic[53] rooted in societal anxieties about rape, hedonism and the increased freedoms of women in modern culture. Goode et al. say it has given a powerful added incentive for the suppression of party drugs,[51] has inappropriately undermined the long-established argument that recreational drug use is purely a consensual and victimless crime. By shining a spotlight on premeditated criminal behavior, Philip Jenkins states that it has relieved the culture from having to explore and evaluate more nuanced forms of male sexual aggression towards people, such as those displayed in date rapes that were not facilitated by the surreptitious administration of drugs.[54]

For similar moral panics around social tensions manifesting via discussion of drugs and sex crime, researchers point to the opium scare of the late 19th century, in which "sinister Chinese" were said to use opium to coerce white women into sexual slavery. Similarly, in the Progressive Era, a persistent urban legend told of white middle-class women being surreptitiously drugged, abducted, and sold into sexual slavery to Latin American brothels.[55][56] This analysis does not contradict instances when date rape drugs are used or sexual trafficking occurs; its focus is on actual prevalence of certain crimes relative to media coverage of it.[editorializing]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Lyman, Michael D. (2006). Practical drug enforcement (3rd ed.). Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC. p. 70. ISBN 0849398088.

- ^ a b "Alcohol Is Most Common 'Date Rape' Drug". Medical News Today. 2007-10-15. Archived from the original on 2010-03-15. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ^ McGregor, Margaret J.; Ericksen, Janet; Ronald, Lisa A.; Janssen, Patricia A.; Van Vliet, Anneke; Schulzer, Michael (December 2004). "Rising Incidence of Hospital-reported Drug-facilitated Sexual Assault in a Large Urban Community in Canada: Retrospective Population-based Study". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 95 (6): 441–5. doi:10.1007/BF03403990. JSTOR 41994426. PMC 6975915. PMID 15622794.

- ^ Elsohly, M. A.; Salamone, S. J. (1999). "Prevalence of Drugs Used in Cases of Alleged Sexual Assault". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 23 (3): 141–6. doi:10.1093/jat/23.3.141. PMID 10369321. S2CID 22935121. NCJ Number 181962.

- ^ a b c d Miller, Richard Lawrence (2002). Drugs of abuse: a reference guide to their history and use. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 168. ISBN 0313318077.

- ^ Scott-Ham, Michael; Burton, Fiona C. (August 2005). "Toxicological findings in cases of alleged drug-facilitated sexual assault in the United Kingdom over a 3-year period". Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine. 12 (4): 175–186. doi:10.1016/j.jcfm.2005.03.009. PMID 16054005.

- ^ Quigley, P.; Lynch, D. M.; Little, M.; Murray, L.; Lynch, A. M.; O'Halloran, S. J. (2009). "Prospective study of 101 patients with suspected drink spiking". Emergency Medicine Australasia. 21 (3): 222–228. doi:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2009.01185.x. PMID 19527282. S2CID 11404683.

- ^ Francis, Ellen (28 October 2021). "Reports of 'needle spiking' in Britain drive young women, students to boycott bars". The Washington Post. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Hui, Sylvia (27 October 2021). "Young women boycott U.K. pubs and nightclubs over needle 'spiking' concerns". Global News. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Gallagher, Conor (27 October 2021). "Gardaí investigate claim woman 'spiked' in nightclub with needle". The Irish Times. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ "Scopolamine: Colombia's Date Rape Drug". Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ^ a b Bechtel, Laura K. (25 October 2010). "Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault". In Holstege, Christopher P.; Neer, Thomas M.; Saathoff, Gregory B.; Furbee, R. Brent (eds.). Criminal poisoning: clinical and forensic perspectives. Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 232. ISBN 978-0763744632.

- ^ a b Pyrek, Kelly (2006). Forensic nursing. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis. p. 173. ISBN 084933540X.

- ^ Smith, Merril D., ed. (2004). Encyclopedia of rape (1. publ. ed.). Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Greenwood Press. p. 226. ISBN 0313326878.

- ^ Karila, Laurent; Novarin, Johanne; Megarbane, Bruno; Cottencin, Olivier; Dally, Sylvain; Lowenstein, William; Reynaud, Michel (1 October 2009). "[Gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB): more than a date rape drug, a potentially addictive drug]". Presse Médicale. 38 (10): 1526–1538. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2009.05.017. ISSN 2213-0276. PMID 19762202.

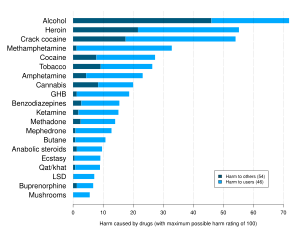

- ^ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- ^ Date Rape. Survive.org.uk (2000-03-20). Retrieved on June 1, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Abbey, A (2002). "Alcohol-related sexual assault: A common problem among college students" (PDF). Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 63 (2): 118–128. doi:10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.118. PMC 4484270. PMID 12022717. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-10-08. Retrieved 2014-06-25.

- ^ Blade, special report. "The Making of an Epidemic", p. 5. October 10, 1993

- ^ Nicholson, M.E. (1998). "Trends in alcohol-related campus violence: Implications for prevention". Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 43 (3): 34–52.

- ^ a b "Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services". Archived from the original on January 16, 2006. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ^ "The Diamondback – Students encounter dangerous date-rape drug". Archived from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ^ Hazelwood, Robert R.; Burgess, Ann Wolbert, eds. (2009). Practical aspects of rape investigation: a multidisciplinary approach (4th ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 446. ISBN 978-1420065046.

- ^ Goldberg, Raymond (2006). Drugs across the spectrum (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 195. ISBN 0495013455.

- ^ ElSohly, Mahmoud A.; Lee, Luen F.; Holzhauer, Lynn B.; Salamone, Salvatore J. (2001). "Analysis of Urine Samples in Cases of Alleged Sexual Assault". In Salamone, Salvatore J. (ed.). Benzodiazepines and GHB: Detection and Pharmacology. Forensic Science and Medicine. Humana Press. pp. 127–144. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-109-1_7 (inactive 2024-09-02). ISBN 978-1-61737-287-2. S2CID 70411731.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of September 2024 (link) - ^ "Watch out for Date Rape Drugs" (PDF). Michigan Department of Community Health. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ^ a b John O. Savino; Brent E. Turvey (2011). Rape investigation handbook (2nd ed.). Waltham, MA: Academic Press. pp. 338–9. ISBN 978-0123860293.

- ^ "Date Rape Drug: List and Side Effects". MedicineNet. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ^ Hazelwood, Robert R.; Burgess, Ann Wolbert, eds. (2009). Practical aspects of rape investigation: a multidisciplinary approach (4th ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 339–446. ISBN 978-1420065046.

- ^ Abadinsky, Howard (June 2010). Drug use and abuse: a comprehensive introduction (7th ed.). Australia: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 169. ISBN 978-0495809913.

- ^ Nordstrom, K (2017). Quick guide to psychiatric emergencies. Springer.

- ^ a b c Miller, Richard Lawrence (2002). Drugs of abuse: a reference guide to their history and use. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 183. ISBN 0313318077.

- ^ Lyman, Michael D. (2006). Practical drug enforcement (3rd ed.). Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC. pp. 72–75. ISBN 0849398088.

- ^ a b Pyrek, Kelly (2006). Forensic nursing. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis. pp. 173–176. ISBN 084933540X.

- ^ Peluso, Daniela; Sinclair, Emily; Labate, Beatriz; Cavnar, Clancy (1 March 2020). "Reflections on crafting an ayahuasca community guide for the awareness of sexual abuse". Journal of Psychedelic Studies. 4 (1): 24–33. doi:10.1556/2054.2020.00124. S2CID 211223286.

- ^ Monroe, Rachel (30 November 2021). "Sexual Assault in the Amazon". The Cut.

- ^ "'I was sexually abused by a shaman at an ayahuasca retreat'". BBC News. 16 January 2020.

- ^ "Ayahuasca Community Guide for the Awareness of Sexual Abuse". Chacruna. 5 November 2018.

- ^ Harper, Nancy (2011). "Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault". Child Abuse and Neglect (PDF). pp. 118–126. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4160-6393-3.00015-4. ISBN 9781416063933.

- ^ Fradella, Fradella; Fahmy, Chantal (2016-02-26). Sex, Sexuality, Law, and (In)justice. Routledge. p. 155. ISBN 9781317528913.

- ^ Zemishlany, Z (2001). "Subjective effects of MDMA ('Ecstasy') on human sexual function". European Psychiatry. 16 (2): 127–30. doi:10.1016/s0924-9338(01)00550-8. PMID 11311178. S2CID 232175685.

- ^ Hornyak, Tim (2011-08-08). "Device serves date-rape drug detection on the rocks". CNET. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- ^ Sage, Adam (2022-02-22). "French students create straw to test drinks for rape drug GHB | World | The Times". The Times of London. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 2022-05-03.

- ^ Sorties à Nances (2022-02-08), "Des étudiantes nantaises inventent la paille antidrogue - Sorties à Nances" [Nantes students invent anti-drug straw - Outings in Nantes], sortiesanantes.com (in French), retrieved 2022-05-03 (Google Translation)

- ^ "What The Roofie-Detecting Nail Polish Gets So Wrong About Date Rape". HuffPost. 2014-08-27. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- ^ "Undercover Colors SipChip: detects Flunitrazepam, Alprazolam, Diazepam, Midazolam, Oxazepam, Temazepam". Undercover Colors. 2018-11-25. Archived from the original on 2022-01-18. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- ^ Fleischmann, Anne (2019-04-11). "German inventors develop bracelet to test drinks for date-rape drugs". euronews. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- ^ Shuster, Beth (June 8, 1996). "Crackdown Sought on 'Date Rape' Drug". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2020-03-09. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Marshall (June 11, 1996). "Drug Zaps Memory of Rape Victims / Sedative suspected in assault of girl, 15". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Jenkins, Philip (1999). Synthetic panics: the symbolic politics of designer drugs. New York, NY [u.a.]: New York University Press. pp. 20 and 161–182. ISBN 0814742440.

- ^ a b Goode, Erich; Ben-Yehuda, Nachman (2009). Moral Panics: The Social Construction of Deviance (2nd ed.). Chichester, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 217. ISBN 978-1405189347.

- ^ Holmes, Cindy; Ristock, Janice L. (2004). "Exploring Discursive Constructions of Lesbian Abuse: Looking Inside and Out". In Shearer-Cremean, Christine; Winkelmann, Carol L. (eds.). Survivor Rhetoric: Negotiations and Narrativity in Abused Women's Language. Toronto [u.a.]: University of Toronto Press. p. 107. doi:10.3138/9781442684836-006. ISBN 0802089739. S2CID 151393377.

- ^ Webber, Craig (2009). Psychology & Crime. London: Sage. p. 67. ISBN 978-1412919425.

- ^ Jenkins, Philip (1999). Synthetic Panics: The Symbolic Politics of Designer Drugs. New York, NY [u.a.]: New York University Press. pp. 161–182. ISBN 0814742440.

- ^ Jenkins, Philip (1999). Synthetic panics: the symbolic politics of designer drugs. New York, NY [u.a.]: New York University Press. p. 176. ISBN 0814742440.

- ^ Dubinsky, Karen (1993). "Discourses of Danger: The Social and Spatial Settings of Violence". Improper Advances: Rape and Heterosexual Conflict in Ontario, 1880–1929. Chicago u.a.: University of Chicago Press. p. 46. ISBN 0226167534. LCCN 92044673.