Romagna

Romagna (Romagnol: Rumâgna) is an Italian historical region that approximately corresponds to the south-eastern portion of present-day Emilia-Romagna in northern Italy.

Etymology

[edit]The name Romagna originates from the Latin name Romania, which originally was the generic name for "land inhabited by Romans", and first appeared on Latin documents in the 5th century AD. It later took on the more specific meaning of "territory subjected to Eastern Roman rule", whose citizens called themselves Romans (Romani in Latin; Ῥωμαῖοι, Rhomaîoi in Greek). Thus the term Romania came to be used to refer to the territory administered by the Exarchate of Ravenna in contrast to other parts of Northern Italy under Lombard rule, named Langobardia or Lombardy.

Location and boundaries

[edit]Romagna is traditionally limited by the Apennines to the south-west, the Adriatic to the east, and the rivers Reno and Sillaro to the north and west. To the southeast, the valley formed by the Conca river has historically formed a buffer region between the regions of Romagna and the Marche.[1]

The region's major cities include Cesena, Faenza, Forlì, Imola, Ravenna, and Rimini. The independent Republic of San Marino is considered by some to be part of the region.

Romagnol culture exerts a considerable influence over the Montefeltro historical region, on the borders between Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, and the Marche. On 15 August 2009, seven municipalities were transferred from the Province of Pesaro and Urbino to the Province of Rimini: Casteldelci, Maiolo, Novafeltria, Pennabilli, San Leo, Sant'Agata Feltria and Talamello.[2] On 17 June 2021, the municipalities of Montecopiolo and Sassofeltrio followed.[3]

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]A number of archaeological sites in the region, such as Monte Poggiolo, show that Romagna has been inhabited since the Paleolithic age.

Umbri and Gauls

[edit]The Umbri, speaking an extinct Italic language called Umbrian, are the first traceable inhabitants of the region. The Etruscans also dwelt in some portions of Romagna.

In the 5th century BC, various Gaulish tribes, most notably the Lingones, Senones and Boii, moved south into Ithe Italian peninsula, and sacked Rome in 390 BC. The Senones subjugated the Umbri and settled in Romagna, extending south to Ancona, with their capital at Sena Gallica (Senigallia). The lands formerly inhabited by the Senones were known as ager Gallicus (Gallic plain) to the Romans.

According to the Italian linguist Giacomo Devoto, there are still a number of Celtic substrata in the Romagnolo dialect.[citation needed]

Roman Republic

[edit]In 295 BC, the Roman Republic won a decisive victory at the Battle of Sentinum against a coalition of Umbris, Senones, Samnites, and Etruscans. To consolidate their victory, the colonia of Ariminum (Rimini) was founded in southern Romagna in 268 BC, alongside the construction of the Via Flaminia, running from Rome to Ariminum.[4][5] Rome was further strengthened by their victory over Celtic tribes at the Battle of Telamon in 225 BC, leading to the Roman hegemony over the new Roman Province of Cisalpine Gaul centred at Mutina (modern Modena).

After the Second Punic War, the pro-Carthaginian Lingones and Senoni were expelled. To consolidate the Roman rule in the region, in 187 BC, the Via Aemilia was completed from Ariminum to Piacentia (Piacenza). A series of colonies were founded along the route; in Romagna, these included Forum Livii (Forlì), Forum Cornellii (Imola), and Forum Popilii (Forlimpopoli). The Lex Julia of 90 BC, following the Social War, granted Roman citizenship to all municipia south of the River Po.

During Sulla's civil war in 82 to 82 BC, most of the colonies supported Gaius Marius. Forum Livii and Caesena (Cesena) were razed to ground, and the region was looted by Lucius Cornelius Sulla's victorious army.

The First Triumvirate divided the Roman Republic along the infamous Rubicon. Most of the colonies in present-day Romagna were ruled by Julius Caesar, with the notable exception of Ariminum, south of the river. In 49 BC, Caesar, who had been residing in Ravenna, led the Legio XIII across the Rubicon, igniting Caesar's civil war.

Roman Empire

[edit]After the decisive Battle of Actium, the reign of Augustus started a centuries-long era of Pax Romana. All of Cisalpine Gaul had been incorporated into the Roman province of Italia. Around 7 BC, Augustus divided all of Italy into eleven regiones, and most of Romagna (except Rimini) was in the eighth, Aemilia.

Towards the end of the 3rd century, Diocletian reordered the Empire into four prefectures, each divided into dioceses, which in turn were divided into provinces. Under the new system, Italy was demoted to a mere Imperial province. Modern Romagna was organized into the Roman province of Flaminia et Picenum in the diocese of Italia Annonaria.

Ravenna, which was surrounded by swamps and marshes, prospered and steadily rose in importance, and a Roman fleet was based at the city. It had developed into a major port on the Adriatic. However, in 330, the capital of the Empire was transferred to Constantinople, so with the fleet that stationed at Ravenna, thus weakened the coastal defence in the Adriatic.

Germanic migrations and Exarchate of Ravenna

[edit]Stepping into the 5th century, the Germanic migrations into the Empire further intensified. In 402, Emperor Honorius even moved the Western Roman Empire's capital from Mediolanum to Ravenna, mainly because of the region's defensive terrain. 8 years later, Alaric I of the Visigoths looted Rome. In 476, Odoacer deposed Romulus in Ravenna, thus marking an end to the Western Empire.

Encouraged by Emperor Zeno, Theodoric the Great led the Ostrogoths into Italy. He entered Ravenna and murdered Odoacer in 493, establishing a twofold kingdom of the Romans and Goths. Under the Ostrogoths Italy was partly restored to its former prosperity.

In 535 Justinian I initiated the Gothic War. It was fought for 20 years, and the Ostrogoths were finally subjugated. The peninsula, depopulated and devastated, was ruled by an exarch from Ravenna. However, Imperial authority was maintained for barely more than a decade. In 568 new Germanic tribes, the Lombards, entered Italy, and established their capital at Pavia. The Empire could barely defend the region around Ravenna and Rome, connected by a narrow strip of land passing through Perugia, as well as a series of coastal cities. The Imperial frontier retreated to Bologna.

In 727 the Lombard King Liutprand renewed war against the Byzantines, taking most of Romagna and besieging Ravenna itself. These territories were returned to the Byzantines in 730. In 737 the king entered Romagna once more and took Ravenna. The exarch, Eutychius, retook the region in 740, with Venetian assistance. Eventually another Lombard king, Aistulf, conquered Romagna once more, and brought an end to the exarchate in 751.

Papal rule

[edit]King Rudolf I of Germany officially ceded Romagna to the Papal States in 1278. However, papal control over the area long remained only nominal. The region was divided among a series of regional lords, such as the Ordelaffi of Forlì or the Malatesta of Rimini, many of them adhering to the Ghibelline party in opposition to the pro-papal Guelphs. This situation started to change in the late-15th century, when after their return to Rome from Avignon in 1378, stronger popes progressively reasserted their authority in the fragmented region. Parts of Romagna were also seized by other powers, including Venice, and most notably the Republic of Florence, which took land up to Forlì and Cervia, building the famous city-fortress of Terra del Sole. The Florentine Romagna remained part of Tuscany until the 1920s.

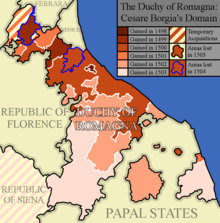

In 1500 Cesare Borgia, illegitimate son of Pope Alexander VI, carved out for himself an ephemeral Duchy of Romagna, but his lands were reabsorbed into the Papal States after his fall. In 1559 the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis divided Romagna between the Farnese family of the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza, the House of Este of the Ferrara, and the Duchy of Modena and Reggio, and the Papal States. The Duchy of Ferrara was later annexed by the Papal States on the extinction of the main d'Este line in 1597, with the cadet branch retaining the Imperial fiefs of Modena and Reggio.

This situation lasted until the French invasion of 1796, which brought bloodshed (the massacre of Lugo, looting, heavy taxation, the destruction of Cesena University) but also innovative ideas in social and political fields. Under Napoleonic rule Romagna received recognition as an entity for the first time, with the creation of the provinces of the Pino (Ravenna) and Rubicone (Forlì). When in 1815 the Congress of Vienna restored the pre-war situation, secret anti-papal societies were formed, and riots broke out in 1820, 1830–31 and 1848.

This opposition was fuelled by the Mazzinian propaganda and the direct action of Giuseppe Garibaldi. Men like Felice Orsini, Piero Maroncelli and Aurelio Saffi were among the protagonists of the Italian Risorgimento.

Post-unification

[edit]However, after joining the unification of Italy in 1860, Romagna was not awarded separate status by the Savoy monarchs, who were afraid of dangerous destabilizing tendencies in the wake of the popular figures cited above.

In the early 20th century the autonomy of Romagna was advocated by Aldo Spallicci, Giuseppe Fuschini, Emilio Lussu and others. A movement proposing separation from Emilia-Romagna was created in the 1990s.

See also

[edit]- Fogheraccia – an annual public bonfire festival in Romagna on the evening of 18 March, the vigil of Saint Joseph's Day,[6][7] especially popular in Rimini[8]

- Lagotto Romagnolo – a dog breed native to Romagna

- Mazapégul – a mischievous nocturnal elf in the folklore of Romagna,[9][10] known for disrupting sleep and tormenting beautiful young girls[9][11][12][13]

References

[edit]- ^ Zaghini, Paolo (16 October 2023). "Sulle rive del Conca, confine che unisce" [On the banks of the Conca, a border that unites]. Chiamami Città (in Italian). Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ "Legge 3 agosto 2009, n. 117" [Law of 3 August 2009, no. 117]. Italian Parliament (in Italian). 3 August 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ "Legge 28 maggio 2021, n. 84" [Law of 28 May 2021, no. 84]. Gazzetta Ufficiale (in Italian). 28 May 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ "La Storia" [History]. Comune di Riccione (in Italian). Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ "Il ponte romano sul Rio Melo a Riccione" [The Roman bridge over the Rio Melo in Riccione]. Famija Arciunesa (in Italian). 1 March 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ Lazzari, Martina (17 March 2024). "Fogheraccia: origine del falò che "incendia" la notte di San Giuseppe" [Fogheraccia: Origin of the bonfire that "alights" St Joseph's night]. RiminiToday (in Italian). Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ Lippi, Giacomo (15 March 2024). "San Giuseppe 2024, i falò si accendono in Romagna: ecco dove" [St Joseph's 2024: The bonfires are lit in Romagna; here's where]. Il Resto del Carlino (in Italian). Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ "18 marzo – La fugaràza 'd San Jusèf" [18 March – St Joseph's bonfire]. Chiamami Città (in Italian). 18 March 2024. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Mazapegul: il folletto romagnolo che ha fatto dannare i nostri nonni" [Mazapegul: The elf from Romagna who ruined our grandparents]. Romagna Republic (in Italian). 21 November 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ Lazzari, Martina (29 October 2023). "Piada dei morti, preparazione e curiosità sulla dolce "piadina" romagnola" [Piada dei morti: Preparation and curiosity about the sweet Romagnol "piadina"]. RiminiToday (in Italian). Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ Campagna, Claudia (28 February 2020). "Mazapegul, il folletto romagnolo" [Mazapegul, the romagnol elf]. Romagna a Tavola (in Italian). Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Mazapègul, il 'folletto di Romagna' al Centro Mercato" [Mazapègul, the 'elf of Romagna' at the Market Centre]. estense.com (in Italian). 13 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ Cuda, Grazia (5 February 2021). "E' Mazapégul" [It's Mazapégul]. Il Romagnolo (in Italian). Retrieved 2 March 2024.