River Thames frost fairs

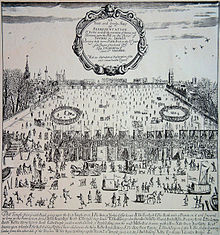

The River Thames frost fairs[1] were held on the tideway of the River Thames in London, England in some winters, starting at least as early as the late 7th century[2] until the early 19th century. Most were held between the early 17th and early 19th centuries during the period known as the Little Ice Age, when the river froze over most often, though still infrequently. During that time the British winter was more severe than it is now, and the river was wider and slower, further impeded by the 19 piers of the medieval Old London Bridge which were removed in 1831.

Even at its peak, in the mid-17th century, the Thames in London froze less often than modern legend sometimes suggests, never exceeding about one year in ten except for four winters between 1649 and 1666. From 1400 until the removal of the medieval London Bridge in 1831, there were 24 winters in which the Thames was recorded to have frozen over at London.[3] The Thames freezes over more often upstream, beyond the reach of the tide, especially above the weirs, of which Teddington Lock is the lowest. The last great freeze of the higher Thames was in 1962–63.[4]

Frost fairs were a rare event even in the coldest parts of the Little Ice Age. Some of the recorded frost fairs were in 695, 1608, 1683–84, 1716, 1739–40, 1789, and 1814. Recreational cold weather winter events were far more common elsewhere in Europe, for example in the Netherlands, where at least many canals often froze over. These events in other countries as well as the winter festivals and carnivals around the world in present times can also be considered frost fairs. However, very few of them have actually used that title.

During the Great Frost of 1683–84, the most severe freeze recorded in England,[5][6][7] the Thames was completely frozen for two months, with the ice reaching a thickness of 11 inches (28 cm) in London. Solid ice was reported extending for miles off the coasts of the southern North Sea (England, France and the Low Countries), causing severe problems for shipping and preventing the use of many harbours.[8]

Historical background

[edit]One of the earliest accounts of the Thames freezing comes from AD 250, when it was frozen solid for six weeks. In 923, the river was open to wheeled traffic for trade and the transport of goods for 13 weeks. In 1410, it lasted for 14 weeks.[citation needed]

The period from the mid-14th century to the 19th century in Europe is called the Little Ice Age because of the severity of the climate, especially the winters. In England, when the ice was thick enough and lasted long enough, Londoners would take to the river for travel, trade, and entertainment, the latter eventually taking the form of public festivals and fairs.

The Thames was broader and shallower in the Middle Ages – it was yet to be embanked, meaning that it flowed more slowly.[9] Moreover, old London Bridge, which carried a row of shops and houses on each side of its roadway, was supported on many closely spaced piers; these were protected by large timber casings which, over the years, were extended – causing a narrowing of the arches below the bridge, thus concentrating the water into swift-flowing torrents. In winter, large pieces of ice would lodge against these timber casings, gradually blocking the arches and acting like a dam for the river at ebb tide.[10][11]

The frost fairs

[edit]AD 695 (first known frost fair)

[edit]The first known frost fair on the River Thames was in AD 695, although it was not known by the title of frost fair. The river froze over for six weeks. Vendors set up booths on the frozen river in which they sold goods.[2]

1608 (first frost fair that was called a frost fair)

[edit]

The first recorded frost fair for which the term "frost fair" was used was in 1608.[2] There were barbers, pubs, fruitsellers and shoemakers, who lit fires inside of their tents to stay warm.[12][unreliable source?] Activities at the frost fair included football,[12] and according to an article published in The Saturday Magazine in 1835, dancing, nine-pin bowling, and unlicensed gambling.[13][unreliable source?]

1683–84

[edit]The most celebrated frost fair occurred in the winter of 1683–84. Activities included horse and coach racing, ice skating, puppet plays and bull-baiting,[14] as well as football, nine-pin bowling, sledding, fox hunting, and throwing at cocks.[15]

John Evelyn's account of the 1683-84 frost fair:

Coaches plied from Westminster to the Temple, and from several other stairs too and fro, as in the streets; sleds, sliding with skeetes, a bull-baiting, horse and coach races, puppet plays and interludes, cooks, tipling and other lewd places, so that it seemed to be a bacchanalian triumph, or carnival on the water.[14]

For sixpence, the printer Croom sold souvenir cards written with the customer's name, the date, and the fact that the card was printed on the Thames; he was making five pounds a day (ten times a labourer's weekly wage). King Charles II bought one. The cold weather was not only a cause for merriment, as Evelyn explained:

The fowls, fish and birds, and all our exotic plants and greens universally perishing. Many parks of deer were destroyed, and all sorts of fuel so dear that there were great contributions to keep the poor alive...London, by reason for the excessive coldness of the air hindering the ascent of the smoke, was so filled with the fuliginous steam of the sea-coal ...that one could hardly breath.[14]

An eye-witness account of the 1683–84 frost:[17]

On the 20th of December, 1688 [misprint for 1683], a very violent frost began, which lasted to the 6th of February, in so great extremity, that the pools were frozen 18 inches thick at least, and the Thames was so frozen that a great street from the Temple to Southwark was built with shops, and all manner of things sold. Hackney coaches plied there as in the streets. There were also bull-baiting, and a great many shows and tricks to be seen. This day the frost broke up. In the morning I saw a coach and six horses driven from Whitehall almost to the bridge (London Bridge) yet by three o'clock that day, February the 6th, next to Southwark the ice was gone, so as boats did row to and fro, and the next day all the frost was gone. On Candlemas Day I went to Croydon market, and led my horse over the ice to the Horseferry from Westminster to Lambeth; as I came back I led him from Lambeth upon the middle of the Thames to Whitefriars' stairs, and so led him up by them. And this day an ox was roasted whole, over against Whitehall. King Charles and the Queen ate part of it.

Thames frost fairs were often brief, scarcely commenced before the weather lifted and the people had to retreat from the melting ice. Rapid thaws sometimes caused loss of life and property. In January 1789, melting ice dragged a ship which was anchored to a riverside public house, pulling the building down and causing five people to be crushed to death.

18th century

[edit]There were frost fairs in 1715–16, 1739–40, and 1789.

Frost fair, 1814 (last frost fair)

[edit]

The frost fair of 1814 began on 1 February, and lasted four days, between Blackfriars Bridge and London Bridge. An elephant was led across the river below Blackfriars.[18] Temperatures had been below freezing every night from 27 December 1813 to 7 February 1814 and numerous Londoners made their way onto the frozen Thames.[19]

Tradesmen of all types set up booths to sell their wares, and pedlars circulated through the crowd.[20] Food and drink was being sold including beef, Brunswick Mum, coffee, gin, gingerbread, hot apples, Old Tom gin, roast mutton, hot chocolate, purl (wormwood ale), and black tea.[15] Activities included dancing[15] and nine-pin bowling.[13]

As the ice broke up starting on 5 February, several people drowned.[21]

Nearly a dozen printing presses were also on the ice, producing commemorative poems.[22] A printer named George Davis published a 124-page book, Frostiana; or A History of the River Thames In a Frozen State: and the Wonderful Effects of Frost, Snow, Ice, and Cold, in England, and in Different Parts of the World Interspersed with Various Amusing Anecdotes. The entire book was typeset and printed in Davis's printing stall which had been set up on the frozen Thames.[23] The book contained an account of the frost, humorous sayings, anecdotes, various weather-related histories and specifics about "skaiting" according to a 1814 review.[24]

This was the last frost fair. The climate was growing milder; old London Bridge was demolished in 1831[25][26][27] and replaced with a new bridge with wider arches, allowing the tide to flow more freely;[28] and the river was embanked in stages during the 19th century, all of which made the river less likely to freeze. There was nearly a frost fair during the severe winter of 1881, with Andrews (1887) saying, "it was expected by many that a Frost Fair would once more be held on the Thames".[2]

Related events

[edit]16th century

[edit]The Thames froze over several times in the 16th century: King Henry VIII travelled from central London to Greenwich by sleigh along the river in 1536, Queen Elizabeth I took to the ice frequently during 1564, to "shoot at marks", and small boys played football on the ice.[11]

Walking from Fulham to Putney 1788–1789

[edit]Soon after Beilby Porteus, Bishop of London, took residence at Fulham Palace in 1788, he recorded that the year was remarkable "for a very severe frost the latter end of the year, by which the Thames was so completely frozen over, that Mrs. Porteus and myself walked over it from Fulham to Putney".[29] The annual register recorded that, in January 1789, the river was "completely frozen over and people walk to and fro across it with fairground booths erected on it, as well as puppet shows and roundabouts".

Legacy

[edit]Engraving

[edit]

In the pedestrian tunnel under the southern end of Southwark Bridge, there is an engraving by Southwark sculptor Richard Kindersley, made of five slabs of grey slate, depicting the frost fair.[30]

The frieze contains an inscription that reads (two lines per slab):

Behold the Liquid Thames frozen o’re,

That lately Ships of mighty Burthen bore

The Watermen for want of Rowing Boats

Make use of Booths to get their Pence & Groats

Here you may see beef roasted on the spit

And for your money you may taste a bit

There you may print your name, tho cannot write

Cause num'd with cold: tis done with great delight

And lay it by that ages yet to come

May see what things upon the ice were done

The inscription is based on handbills[31] printed on the Thames during the frost fairs.

In popular culture

[edit]An early chapter of the novel Orlando: A Biography by Virginia Woolf takes place on the frozen River Thames during the Frost Fair of 1608.

In the historical mystery, The True Confessions of a London Spy by Katherine Cowley key events of the plot occur at the Frost Fair of 1814.

In the book, “One Snowy Night” by Amanda Grange, the characters go to the Frost Fair of 1814.

In the Doctor Who episode "A Good Man Goes to War," River Song encounters Rory Williams as she is returning to her cell in the Stormcage Containment Facility. She tells him that she has just been to 1814 for the last of the Great Frost Fairs. The Doctor had taken her there for ice-skating on the river Thames. "He got Stevie Wonder to sing for me under London Bridge," she says. When Rory expresses surprise that Stevie Wonder sang in 1814, River cautions him that he must never tell the singer that he did.[32]

The Doctor Who episode "Thin Ice" is set during the final frost fair in 1814, and includes a reference to the elephant crossing stunt.[33]

See also

[edit]- Arctic oscillation

- Chipperfield's Circus - started at the 1684 frost fair and continues to this day in its 7th generation.

- Dalton Minimum

- Frost fair definition in Wiktionary

- Frozen Strait

- Great Frost of 1709

- Maunder Minimum

- Spörer Minimum

Notes

[edit]- ^ https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=599805001&objectId=3199037&partId=1 Erra Paters Prophesy or Frost Faire 1684/3

- ^ a b c d Lockwood, Mike; Owens, Mat; Hawkins, Ed; Jones, Gareth S.; Usoskin, Ilya (2017). "Frost fairs, sunspots and the Little Ice Age". Astronomy & Geophysics. 58 (2): 2.17–2.23. doi:10.1093/astrogeo/atx057.

- ^ Lamb 1977

- ^ Windsor history

- ^ Appleby, Andrew B. (Spring 1980). "Epidemics and Famine in the Little Ice Age". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 10 (4 History and Climate: Interdisciplinary Explorations): 643–663. doi:10.2307/203063. JSTOR 203063.

- ^ Manley, Gordon (2011). "1684: The Coldest Winter in the English Instrumental Record". Weather. 66 (5): 133–136. Bibcode:2011Wthr...66..133M. doi:10.1002/wea.789.

- ^ Manley, G. (1974). "Central England temperatures: monthly means 1659 to 1973" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 100 (425): 389–405. Bibcode:1974QJRMS.100..389M. doi:10.1002/qj.49710042511.

- ^ "No. 1900". The London Gazette. 31 January 1683. p. 1.

- ^ The London Mercury Vol.XIX No.113

- ^ Manley, Gordon (May 1972). Climate and the British Scene. Collins. p. 290. ISBN 978-0002130448.

- ^ a b Schneer 2005, p. 72

- ^ a b "The Thames Frost Fairs". Historic UK. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Sports & Games – 1608–1814 Skittles or Nine Pins on Ice at Frost Fairs on the frozen Thames". Western Public Pleasure Gardens – Public Spaces in Early Europe. 17 December 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^ a b c Hudson 1998, quoting Evelyn

- ^ a b c de Castella, Tom (28 January 2014). "Frost fair: When an elephant walked on the frozen River Thames". BBC News. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ William Andrews (1887). Famous Frosts and Frost Fairs in Great Britain: Chronicled from the Earliest to the Present Time. G. Redway. pp. 16–17.

- ^ "HARD FROSTS IN ENGLAND". The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. 7 February 1829. Retrieved 14 January 2010 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Curious Story of River Thames Frost Fairs". Thames Leisure. 13 June 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ Selli, Fabrizio (27 November 2018). "All the fun of the Frost Fair: why, when and how did Londoners party on the ice?". Museum of London. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ Shute, Joe (23 December 2013). "The Big Freeze that became an unforgettable Frost Fair". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ Milmo, Cahal (31 January 2014). "When winter really was winter: the last of the London Frost Fairs". The Independent. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ "The last Thames frost fair". The History Press. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ Printed ‘Frost Fair’ ephemera in the University Library

- ^ The British Critic, and Quarterly Theological Review, p. 221

- ^ Review of "Professional Survey of the Old and New London Bridges" in The Examiner, issue 1232, 11 Sep 1831 (London)

- ^ Barge crashes into bridge ruins, in the Morning Chronicle, issue 19547, 20 Apr 1832 (London)

- ^ Schneer 2005, p. 70

- ^ Schneer 2005, p. 73

- ^ Porteus 1806, p. 27

- ^ "City Insights page on Kindersley's frieze". Archived from the original on 28 June 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Ephemera, by Maurice Rickards, Michael Twyman, Sally De Beaumont, p. 154

- ^ Martin, Dan (29 April 2017). "Doctor Who recap: series 36, episode three – Thin Ice". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ Hogan, Michael (29 April 2017). "Doctor Who: Thin Ice, series 10 episode 3 review - a touch of nostalgia keeps old-fashioned caper rollicking along". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

Sources

[edit]- Britton, John; Brayley, Edward Wedlake; Brewer, James Norris; et al. (1816). The Beauties of England and Wales, Or, Delineations, Topographical, Historical, and Descriptive, of Each County. Vol. X. Thomas Maiden. p. 83.

- Currie, Ian (1996). Frost, Freezes and Fairs: Chronicles of the Frozen Thames and Harsh Winters in Britain from 1000 A.D. Coulsdon, Surrey: Frosted Earth. ISBN 978-0-9516710-8-5.

- Davis, George. Frostiana; Or a History of the River Thames in a Frozen State. (London: printed and published on the Ice on the River Thames, 12mo., 5 February 1814)

- Drower, George. 'When the Thames froze', The Times, 30 December 1989

- Evelyn, John (1684). "An Abstract of a Letter from the Worshipful John Evelyn Esq; Sent to One of the Secretaries of the R. Society concerning the Dammage [sic] Done to His Gardens by the Preceding Winter". Philosophical Transactions. 14 (155–166): 559–63. doi:10.1098/rstl.1684.0025. JSTOR 102048. S2CID 186213994.

- Hudson, Roger (1998). London: Portrait of a City. London: The Folio Society. OCLC 40826947.

- Humphreys, Helen (2007). The Frozen Thames. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-4144-0.

- Lamb, H.H. (1977). "Appendix to Part III: Table App. V.6 and App. V.7". Climate: Present, past and future. Vol. 2. London: Methuen. pp. 568–570. ISBN 978-0064738811.

- Porteus, Dr. Beilby (1806). A Brief Description of Three Favourite Country Residences. Cambridge: privately printed in a limited edition.

- Reed, Nicholas (2002). Frost Fairs on the Frozen Thames. Folkestone: Lilburne Press. ISBN 978-1-901167-09-2.

- Schneer, Jonathan (2005). The Thames: England's River. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-86139-7.

External links

[edit]- "Frost Fair Mug". Glass. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- Print of The Frost Fair, 1684: "Great Britains Wonder"

- Historical Weather Events, 1650–1699

- Climate of England

- Christmas markets in the United Kingdom

- History of the River Thames

- Social history of London

- Fairs in England

- Winter festivals in the United Kingdom

- Festivals established in the 17th century

- Recurring events established in 1608

- 1608 establishments in England

- Winter events in England

- Christmas in England

- 1814 in London