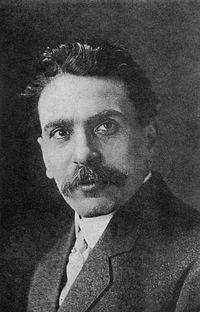

David Pinski

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2010) |

David Pinski | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 5, 1872 Mogilev, Russian Empire |

| Died | August 11, 1959 (aged 87) Israel |

| Occupation | Writer |

David Pinski (Yiddish: דוד פּינסקי; April 5, 1872 – August 11, 1959) was a Yiddish language writer, probably best known as a playwright. At a time when Eastern Europe was only beginning to experience the Industrial Revolution, Pinski was the first to introduce to its stage a drama about urban Jewish workers; a dramatist of ideas, he was notable also for writing about human sexuality with a frankness previously unknown to Yiddish literature. He was also notable among early Yiddish playwrights in having stronger connections to German language literary traditions than Russian.

Early life

[edit]He was born in Mogilev, in the Russian Empire (present-day Belarus), and was raised in nearby Vitebsk. At first destined for a career as a rabbi, he had achieved an advanced level in Talmudic studies by the age of 10.[1] At 19 he left home, originally intending to study medicine in Vienna, Austria, but a visit to I.L. Peretz in Warsaw (then also under Russian control, now the capital of Poland) convinced him to pursue a literary career instead. He briefly began studies in Vienna (where he also wrote his first significant short story, "Der Groisser Menshenfreint"—"The Great Philanthropist"), but soon returned to Warsaw, where he established a strong reputation as a writer and as an advocate of Labor Zionism, before moving to Berlin, Germany in 1896 and to New York City in 1899.

He pursued a doctorate at Columbia University; however, in 1904, having just completed his play Family Tsvi on the day set for his Ph.D. examination, he failed to show up for the exam, and never finished the degree.[1]

Works

[edit]

His naturalistic tragedy Isaac Sheftel (1899) tells of a technically creative weaver, whose employer scorns him, but exploits his inventions. He finally smashes the machines he has created, and falls into drunken self-destruction. Like many of Pinski's central characters, he is something other than a traditional hero or even a traditional tragic hero.

His dark comedy Der Oytser (The Treasure), written in Yiddish 1902-1906 but first staged in German, by Max Reinhardt in Berlin in 1910, tells of a sequence of events in which the people of a town dig up and desecrate their own graveyard because they have come to believe there is a treasure buried somewhere in it. Rich and poor, secular and religious, all participate in the frenzy; a supernatural climax involves the souls of the dead, annoyed by the disruption.

Family Tsvi (1904), written in the wake of the Kishinev pogrom, is a call for Jews not to passively accept violence against them. In this tragedy, various Jews—a religious zealot, a socialist from the Bund, a Zionist, and a disillusioned assimilationist—resist the onslaught in different ways, and for different ideologies, but they all resist. The play could not be officially published openly performed in Imperial Russia, but circulated there surreptitiously, and was even given clandestine amateur productions.

Yenkel der Shmid (Yankel the Smith, 1906) set a new level of frankness in Yiddish-language theater in dealing with sexual passions. Although Yiddish theater was more open to such themes than the English-language theater of the same era, it had mostly entered by way of works translated from miscellaneous European languages. The central couple of the play must balance their passion for each other against their marriages to other people. Ultimately, both return to their marriages, in what Sol Liptzin describes as "an acceptance of family living that neither negated the joy of the flesh nor avoided moral responsibility". [Liptzin, 1972, 86] A film based on the play was made in 1938, filmed at a Catholic monastery in New Jersey; it starred Moyshe Oysher and Florence Weiss, was the film premiere of Herschel Bernardi (playing Yankel as a boy), and is also known as The Singing Blacksmith. It has also been adapted by Caraid O'Brien as the English-language play Jake the Mechanic.

He continued to explore similar themes in a series of plays, Gabri un di Froyen (Gabri and the Women, 1908), Mary Magdalene (1910), and Professor Brenner (1911), the last of which deals with an older man in love with a young woman, again breaking Jewish theatrical tradition, because such relationships had always been considered acceptable in arranged marriages for financial or similar reasons, but socially taboo as a matter of emotional fascination. "Professor Brenner" has been translated into English by Ellen Perecman and was presented by New Worlds Theatre Project in November 2015 in a production directed by Paul Takacs at HERE Arts Centre with David Greenspan in the leading role. The English script will be available at www.newworldsproject.org in December 2015.[2]

During this same period, the one-act messianic tragedy Der Eybiker Yid (The Eternal Jew, 1906) is set at the time of the destruction of the Second Temple. A messiah is born on the same day as the destruction of the Temple, but borne away in a storm; a prophet must wander the Earth searching for him. In Moscow, in 1918 this was to be the first play ever performed by the Habima Theater, now the national theater of Israel. He revisited a similar theme in 1919 in Der Shtumer Meshiekh (The Mute Messiah); he would revisit messianic themes in further plays about Simon Bar-Kokhba, Shlomo Molcho, and Sabbatai Zevi.

His work took a new turn with the highly allegorical Di Bergshtayger (The Mountain Climbers, 1912); the "mountain" in question is life itself.

During the period between the World Wars, he wrote numerous plays, mostly on biblical subjects, but continuing to engage with many of his earlier themes. For example, King David and His Wives (1923) looks at the biblical David at various points in his life: a proud, naively idealistic, pious youth; a confident warrior; a somewhat jaded monarch; and finally an old man who, seeing his youthful glory reflected in the beautiful Abishag, chooses not to marry her, so he can continue to see that idealized reflection. During this period, Pinski also undertook a large and fanciful fiction project: to write a fictional portrait of each of King Solomon's thousand wives; between 1921 and 1936, he completed 105 of these stories.

During this period he also undertook the major novels Arnold Levenberg: Der Tserisener Mentsh (Arnold Levenberg: The Split Personality, begun 1919) and The House of Noah Edon which was published in English translation in 1929; the Yiddish original was published in 1938 by the Wydawnictvo ("Publishers") Ch. Brzozo, Warsaw.[3] The former centers on an Uptown, aristocratic German Jew, who is portrayed as an overefined and decadent, crossing paths with, but never fully participating in, the important events and currents of his time. An English translation by Isaac Goldberg was published in 1928 by Simon and Schuster.[4] The latter is a multi-generational saga of a Lithuanian Jewish immigrant family, an interpretation of assimilation modeled on Peretz's Four Generations—Four Testaments.[5]

Emigration

[edit]In 1949 he emigrated to the new state of Israel where he wrote a play about Samson and one about King Saul. However, this was a period in which Yiddish theater barely existed anywhere (even less so than today), and these were not staged.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Goldberg, Isaac (1918). "New York's Yiddish writers". The Bookman. Vol. 46. pp. 684-689; on Pinski, pp. 684-686. Electronic version via Library of Congress. Retrieved 2017-07-03.

- ^ Ellen

- ^ Photocopy of title and publication page in possession of editor to be scanned and uploaded shortly

- ^ Lambert, Joshua (2010). American Jewish Fiction: A JPS Guide. Jewish Publication Society. p. 34. ISBN 9780827610026.

- ^ Liptzin, Solomon (1985). A History of Yiddish Literature. Jonathan David. p. 140.

Sources

[edit]- Liptzin, Sol, A History of Yiddish Literature, Jonathan David Publishers, Middle Village, NY, 1972, ISBN 0-8246-0124-6, 84 et. seq., 136 et. seq.

External links

[edit]- Works by David Pinski at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about David Pinski at the Internet Archive

- Works by David Pinski at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Singing Blacksmith at IMDb

- David Pinski at the Internet Broadway Database

- Papers of David Pinski.; RG 204; YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York, NY.

- David Pinski (1872-1959) Papers.; P-649; American Jewish Historical Society, New York, NY.

- Pinski visits Vilna and joins the debate between Yiddish and Hebrew supporters

- 1872 births

- 1959 deaths

- People from Mogilev

- People from Mogilyovsky Uyezd (Mogilev Governorate)

- Belarusian Jews

- Jewish socialists

- Israeli people of Belarusian-Jewish descent

- American people of Belarusian-Jewish descent

- American dramatists and playwrights

- Yiddish-language dramatists and playwrights

- Israeli male dramatists and playwrights

- Jewish American dramatists and playwrights

- American emigrants to Israel

- Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United States