Korean conflict

| Korean conflict | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War in Asia (until 1991) | |||||||||

The Korean DMZ, viewed from the north | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Former

|

Former

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||||

| See Korean War for details of belligerents during the war. | |||||||||

The Korean conflict is an ongoing conflict based on the division of Korea between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) and South Korea (Republic of Korea), both of which claim to be the sole legitimate government of all of Korea. During the Cold War, North Korea was backed by the Soviet Union, China, and other allies, while South Korea was backed by the United States, United Kingdom, and other Western allies.

The division of Korea by the United States and the Soviet Union occurred in 1945 after the defeat of Japan ended Japanese rule of Korea, and both superpowers created separate governments in 1948. Tensions erupted into the Korean War, which lasted from 1950 to 1953. When the war ended, both countries were devastated, but the division remained. North and South Korea continued a military standoff, with periodic clashes. The conflict survived the end of the Cold War and is still ongoing. It is now considered one of the 10 frozen conflicts of the world and is considered one of the oldest, along with the Sino-Taiwanese conflict.

The U.S. maintains a military presence in the South to assist South Korea in accordance with the ROK–U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty. In 1997, U.S. President Bill Clinton described the division of Korea as the "Cold War's last divide".[1] In 2002, U.S. President George W. Bush described North Korea as a member of an "axis of evil".[2][3] Facing increasing isolation, North Korea developed missile and nuclear capabilities.

Following heightened tension throughout 2017, and some parts of 2018, 2018 saw North Korea, South Korea and the U.S. holding a series of summits, which promised peace and nuclear disarmament. This led to the Panmunjom Declaration on 27 April 2018, when the North and the South agreed to work together to denuclearize the peninsula, improve inter-Korean relations, end the conflict officially, and move towards the peaceful reunification. In subsequent years, diplomatic efforts faltered and military confrontation returned to the fore.

The Korean border remains the most militarized private area in the world with the presence of the Korean People's Army in north; the Forces of the Republic of Korea and the United States Forces Korea (highlighted notably through the Combined Forces) in south and the presence of the forces of United Nations in the Korean Demilitarized Zone (JSA and Camp Bonifas).

Background

[edit]Korea was annexed by the Empire of Japan on 22 August 1910, and ruled by it until 2 September 1945. During the Japanese occupation of Korea, nationalist and radical groups emerged, mostly in exile, to struggle for independence. Divergent in their outlooks and approaches, these groups failed to unite into a single national movement.[4][5] Based in China, the Korean Provisional Government failed to obtain widespread recognition.[6] The many leaders advocating for Korean independence included the conservative and U.S.-educated Syngman Rhee, who lobbied the U.S. government, and the Communist Kim Il Sung, who fought a guerrilla war against the Japanese from neighboring Manchuria.[7]

Following the end of the occupation, many high-ranking Koreans were accused of collaborating with Japanese imperialism.[8] An intense and bloody struggle between various figures and political groups aspiring to lead Korea ensued.[9]

Division of Korea (1945–1949)

[edit]On 9 August 1945, as agreed by the Allies at the Potsdam Conference, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and advanced into Korea. The U.S. government requested that the Soviet advance stop at the 38th parallel. The U.S. forces were to occupy the area south of the 38th parallel, including the capital, Seoul. This division of Korea into two zones of occupation was incorporated into General Order No. 1, which was given to Japanese forces after the surrender of Japan on 15 August 1945. On 24 August 1945, the Red Army entered Pyongyang and established a military government over Korea north of the parallel. American forces landed in the south on 8 September 1945, and established the U.S. Army Military Government in Korea.[10]

The Allies had originally envisaged a joint trusteeship which would steer Korea towards independence, but most Korean nationalists wanted independence immediately.[11] Meanwhile, the wartime co-operation between the Soviet Union and the U.S. deteriorated as the Cold War took hold. Both occupying powers began promoting into positions of authority Koreans aligned with their side of politics and marginalizing their opponents. Many of these emerging political leaders were returning exiles with little popular support.[12][13] In North Korea, the Soviet Union supported Korean communists. Kim Il Sung, who from 1941 had served in the Soviet Army, became the major political figure.[14] Society was centralized and collectivized, following the Soviet model.[15] Politics in the South were more tumultuous, but the strongly anti-communist Syngman Rhee, who had been educated in the U.S., was positioned as the most prominent politician.[16]

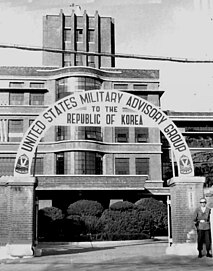

In South Korea, a general election was held on 10 May 1948. The Republic of Korea (or ROK) was established with Syngman Rhee as president, and formally replaced the U.S. military occupation on 15 August. In North Korea, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (or DPRK) was declared on 8 September, with Kim Il Sung, as prime minister. Soviet occupation forces left the DPRK on 10 December 1948. U.S. forces left the ROK the following year, though the U.S. Korean Military Advisory Group remained to train the Republic of Korea Army.[17] The new regimes even adopted different names for Korea: the North choosing Choson, and the South Hanguk.[18]

Both opposing governments considered themselves to be the government of the whole of Korean Peninsula (as they do to this day), and both saw the division as temporary.[19][20] Kim Il Sung lobbied Stalin and Mao for support in a war of reunification, while Syngman Rhee repeatedly expressed his desire to conquer the North.[21][22] In 1948, North Korea, which had almost all the generators, turned off the electricity supply to the South.[23] In the lead-up to the outbreak of civil war, there were frequent clashes along the 38th parallel, especially at Kaesong and Ongjin, initiated by both sides.[24][25]

Throughout this period there were uprisings in the South, such as the Jeju Uprising and the Yeosu–Suncheon Rebellion, that were brutally suppressed. In all, over one hundred thousand people died in fighting across Korea before the Korean War began.[26]

Korean War (1950–1953)

[edit]

By 1950, North Korea had clear military superiority over the South. The Soviet occupiers had armed it with surplus weaponry and provided training. Many troops returning to North Korea were battle-hardened from their participation in the Chinese Civil War, which had just ended.[27][28] Kim Il Sung expected a quick victory, predicting that there would be pro-communist uprisings in the South and that the U.S. would not intervene.[29] Rather than perceiving the conflict as a civil war, however, the West saw it in Cold War terms as communist aggression, related to recent events in China and Eastern Europe.[30]

North Korea invaded the South on 25 June 1950, and swiftly overran most of the country. In September 1950 United Nations Command, led by the U.S., intervened to defend the South, and following the Incheon Landing and breakout from the Pusan Perimeter, rapidly advanced into North Korea. As the UN force neared the border with China, Chinese forces intervened on behalf of North Korea, shifting the balance of the war again. Fighting ended on 27 July 1953, with an armistice that approximately restored the original boundaries between North and South Korea.[22]

Korea was devastated. Around three million civilians and soldiers had been killed. Seoul was in ruins, having changed hands four times. Several million North Korean refugees fled to the South.[31] Almost every substantial building in North Korea had been destroyed.[32][33] As a result, North Koreans developed a deep-seated antagonism towards the U.S.[31]

Armistice (27 July 1953)

[edit]Negotiations for an armistice began on 10 July 1951, as the war continued. The main issues were the establishment of a new demarcation line and the exchange of prisoners. After Stalin died, the Soviet Union brokered concessions which led to an agreement on 27 July 1953.[34]

President Syngman Rhee opposed the armistice because it left Korea divided. As negotiations drew to a close, he attempted to sabotage the arrangements for the release of prisoners, and led mass rallies against the armistice.[35] He refused to sign the agreement but reluctantly agreed to abide by it.[36]

The armistice inaugurated an official ceasefire but did not lead to a peace treaty for two Koreas.[37] It established the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), a buffer zone between the two sides, that intersected the 38th parallel but did not follow it.[36] Despite its name, the border was, and continues to be, one of the most militarized in the world.[31]

North Korea announced that it would no longer abide by the armistice at least six times, in the years 1994, 1996, 2003, 2006, 2009, and 2013.[38][39]

Cold War period (1953–1991)

[edit]After the war, the Chinese forces left, but U.S. forces remained in the South. Sporadic conflict continued. The North's occupation of the South left behind a guerrilla movement that persisted in the Cholla provinces.[31] On 1 October 1953, the United States and South Korea signed a defense treaty.[40] In 1958, the United States stationed nuclear weapons in South Korea.[41] In 1961, North Korea signed mutual defense treaties with the USSR and China.[42] In the Sino-North Korean Mutual Aid and Cooperation Friendship Treaty, China pledged to render immediate military and other assistance by all means to North Korea against any outside attack.[43] During this period, North Korea was described by former CIA director Robert Gates to be the "toughest intelligence target in the world".[44] Alongside the military confrontation, there was a propaganda war, including balloon propaganda campaigns.[45]

The opposing regimes aligned themselves with opposing sides in the Cold War. Both sides received recognition as the legitimate government of Korea from the opposing blocs.[46][47] South Korea became a strongly anti-Communist military dictatorship.[48] North Korea presented itself as a champion of orthodox Communism, distinct from the Soviet Union and China. The regime developed the doctrine of Juche or self-reliance, which included extreme military mobilization.[49] In response to the threat of nuclear war, it constructed extensive facilities underground and in the mountains.[50][23] The Pyongyang Metro opened in the 1970s, with the capacity to double as bomb shelter.[51] Until the early 1970s, North Korea was an economic equal of the South.[52]

South Korea was heavily involved in the Vietnam War.[53] Hundreds of North Korean fighter pilots went to Vietnam, shooting down 26 U.S. aircraft. Teams of North Korean psychological warfare specialists targeted South Korean troops, and Vietnamese guerrillas were trained in the North.[54]

Tensions between North and South escalated in the late 1960s with a series of low-level armed clashes known as the Korean DMZ Conflict. In 1966, Kim declared "liberation of the south" to be a "national duty".[55] In 1968, North Korean commandos launched the Blue House raid, an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate the South Korean President Park Chung Hee. Shortly after, the American spy ship USS Pueblo was captured by the North Korean navy.[56] The Americans saw the crisis in terms of the global confrontation with Communism, but, rather than orchestrating the incident, the Soviet government was concerned by it.[57] The crisis was initiated by Kim, inspired by Communist successes in the Vietnam War.[58]

In 1967, Korean-born composer Isang Yun was kidnapped in West Germany by South Korean agents and imprisoned in South Korea on the charge of spying for the North. He was released after an international outcry.[59]

In 1969, North Korea shot down a U.S. EC-121 spy plane over the Sea of Japan, killing all 31 crew on board, which constituted the largest single loss of U.S. aircrew during the Cold War.[60] In 1969, Korean Air Lines YS-11 was hijacked and flown to North Korea. Similarly, in 1970, the hijackers of Japan Airlines Flight 351 were given asylum in North Korea.[61] In response to the Blue House raid, the South Korean government set up a special unit to assassinate Kim Il Sung, but the mission was aborted in 1972.[62] In the 1970s, South Korea pursued its own nuclear weapons, but was discouraged by the US.[63]

In 1974, a North Korean sympathizer attempted to assassinate President Park and killed his wife, Yuk Young-soo.[66] In 1976, the Panmunjeom Axe incident led to the death of two U.S. Army officers in the DMZ and threatened to trigger a wider war.[67][68] In the 1970s, North Korea kidnapped a number of Japanese citizens.[61]

In 1976, in now-declassified minutes, U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense William Clements told Henry Kissinger that there had been 200 raids or incursions into North Korea from the South, though not by the U.S. military.[69] According to South Korean politicians who have campaigned for compensation for the survivors, more than 7,700 secret agents infiltrated North Korea from 1953 to 1972, of which about 5,300 are believed not to have returned.[70] Details of only a few of these incursions have become public, including raids by South Korean forces in 1967 that had sabotaged about 50 North Korean facilities.[71] Other missions included targeting advisers from China and the Soviet Union in order to undermine relations between North Korea and its allies.[72]

The East German leader, Erich Honecker, who visited in 1977, was one of Kim Il Sung's closest foreign friends.[73] In 1986, East Germany and North Korea signed an agreement on military co-operation.[74] Kim was also close to maverick Communist leaders, Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia, and Nicolae Ceaușescu of Romania.[75] Libyan Leader Muammar Gaddafi met with Kim Il Sung and was a close ally of the DPRK.[76][77] North Korea began to play a part in the global radical movement, forging ties with such diverse groups as the Black Panther Party of the U.S.,[78] the Workers' Party of Ireland,[79] and the African National Congress.[80] As it increasingly emphasized its independence, North Korea began to promote the doctrine of Juche as an alternative to orthodox Marxism-Leninism and as a model for developing countries to follow.[81]

When North-South dialogue started in 1972, North Korea began to receive diplomatic recognition from countries outside the Communist bloc. Within four years, North Korea was recognized by 93 countries, on par with South Korea's recognition by 96 countries. North Korea gained entry into the World Health Organization and, as a result, sent its first permanent observer missions to the UN.[82] In 1975, it joined the Non-Aligned Movement.[83]

During the 1970s, both North and South began building up their military capacity.[84] It was discovered that North Korea had dug tunnels under the DMZ which could accommodate thousands of troops.[85] Alarmed at the prospect of U.S. disengagement, South Korea began a secret nuclear weapons program which was strongly opposed by Washington.[86]

In 1977, U.S. President Jimmy Carter proposed the withdrawal of troops from South Korea. There was a widespread backlash in America and in South Korea, and critics argued that this would allow the North to capture Seoul. Carter postponed the move, and his successor Ronald Reagan reversed the policy, increasing troop numbers to forty-three thousand.[87] After Reagan supplied the South with F-16 fighters, and after Kim Il Sung visited Moscow in 1984, the USSR recommenced military aid and co-operation with the North.[88]

Unrest in South Korea came to a head with the Gwangju Uprising in 1980. The dictatorship equated dissent with North Korean subversion. On the other hand, some young protesters viewed the U.S. as complicit in political repression and identified with the North's nationalist propaganda.[89][90]

In 1983, North Korea carried out the Rangoon bombing, a failed assassination attempt against South Korean President Chun Doo-hwan while he was visiting Burma.[91] The bombing of Korean Air Flight 858 in 1987, in the lead-up to the Seoul Olympics, led to the U.S. government placing North Korea on its list of terrorist countries.[92][93] North Korea launched a boycott of the Games, supported by Cuba, Ethiopia, Albania and the Seychelles.[94]

In 1986, former South Korean foreign minister Choe Deok-sin defected to North Korea, becoming a leader of the Chondoist Chongu Party.[95]

In the 1980s, the South Korean government built a 98-metre (322 ft)-tall flagpole in the village of Daeseong-dong in the DMZ. In response, North Korea built a 160-metre (520 ft)-tall flagpole in the nearby village of Kijŏng-dong.[45]

Isolation and confrontation (1991–2017)

[edit]

As the Cold War ended, North Korea lost the support of the Soviet Union and plunged into an economic crisis. With the death of leader Kim Il Sung in 1994,[96] there were expectations that the North Korean government could collapse and the peninsula would be reunified.[97][98] US nuclear weapons were removed from South Korea.[63]

In 1994, suspecting that North Korea was developing nuclear weapons, U.S. President Bill Clinton considered bombing North Korea's Yongbyon nuclear reactor, but he later dismissed this option when he was advised that if war broke out, it could cost 52,000 U.S. and 490,000 South Korean military casualties in the first three months, as well as a large number of civilian casualties.[99][100] Instead, in 1994, the U.S. and North Korea signed an Agreed Framework, which aimed to freeze North Korea's nuclear program. In 1998, South Korean President Kim Dae-jung initiated the Sunshine Policy, which aimed to foster better relations with the North.[101] However, in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, U.S. President George W. Bush denounced the policy, and in 2002 branded North Korea a member of an "Axis of Evil".[2][3] Six-party talks involving North and South Korea, the United States, Russia, Japan, and China commenced in 2003 but failed to achieve a resolution. In 2006, North Korea announced it had successfully conducted its first nuclear test.[102] The Sunshine Policy was formally abandoned by South Korean President Lee Myung-bak after his election in 2007.[103]

In the start of the 21st century, it was estimated that the concentration of firepower in the area between Pyongyang and Seoul was greater than that in central Europe during the Cold War.[104] The North's Korean People's Army was numerically twice the size of South Korea's military and had the capacity to devastate Seoul with artillery and missile bombardment. South Korea's military, however, was assessed as being technically superior in many ways.[105][106] U.S. forces remained in South Korea and carried out annual military exercises with South Korean forces, including Key Resolve, Foal Eagle, and Ulchi-Freedom Guardian. These were routinely denounced by North Korea as acts of aggression.[107][108][109] Between 1997 and 2016, the North Korea government accused other governments of declaring war against it 200 times.[110] Analysts have described the U.S. garrison as a tripwire ensuring American military involvement, but some have queried whether sufficient reinforcements would be forthcoming.[111]

During this period, two North Korean submarines were captured after being stranded on the South Korean coast, one near Gangneung in 1996 and one near Sokcho in 1998. In December 1998, the South Korean navy sank a North Korean semi-submersible in the Battle of Yeosu. In 2001, the Japanese Coast Guard sank a North Korean spy ship in the Battle of Amami-Ōshima.

South Korea ceased sending "North Korea Demolition Agents" to raid the North in the early 2000s.[72][112]

Conflict intensified near the disputed maritime boundary known as the Northern Limit Line in the Yellow Sea. In 1999 and 2002, there were clashes between the navies of North and South Korea, known as the First and Second battle of Yeonpyeong. On 26 March 2010, a South Korean naval vessel, the ROKS Cheonan, sank, near Baengnyeong Island in the Yellow Sea and a North Korean torpedo was blamed. On 23 November 2010, in response to a joint military exercise, North Korea fired artillery at South Korea's Greater Yeonpyeong island in the Yellow Sea, and South Korea returned fire.

In 2013, amidst tensions about its missile program, North Korea forced the temporary shutdown of the jointly operated Kaesong Industrial Region.[113] The zone was shut again in 2016.[114] A South Korean parliamentarian was convicted of plotting a campaign of sabotage to support the North in 2013 and jailed for 12 years.[115] In 2014, according to the New York Times, U.S. President Barack Obama ordered the intensification of cyber and electronic warfare to disrupt North Korea's missile testing,[116] but this account has been disputed by analysts from the Nautilus Institute.[117]

In 2016, in the face of protests, South Korea decided to deploy the U.S. THAAD anti-missile system in response to nuclear and missile threats by North Korea.[118][119] After North Korea's fifth nuclear test in September 2016, it was reported that South Korea had developed a plan to raze Pyongyang if there were signs of an impending nuclear attack from the North.[120] A North Korean numbers station started broadcasting again, after a break of 16 years, apparently sending coded messages to agents in the South.[45] As South Korea was convulsed by scandal, North Korea enthusiastically supported the removal of President Park Geun-hye, intensifying leaflet drops.[121] In turn, Park's supporters accused the opposition Liberty Korea Party of basing its logo on Pyongyang's Juche Tower.[122]

In March 2017, it was reported that the South Korean government had increased the rewards to North Korean defectors who brought classified information or military equipment with them.[123] It was also reported that, in 2016, North Korea hackers had stolen classified South Korean military data, including a plan for the killing of Kim Jong Un. According to cybersecurity experts, North Korea maintained an army of hackers trained to disrupt enemy computer networks and steal both money and sensitive data. In the previous decade, it was blamed for numerous cyber-attacks and other hacking attacks in South Korea and elsewhere,[124] including the hack of Sony Pictures supposedly in retaliation for the release of the 2014 film The Interview, which depicts the assassination of Kim Jong Un.[125]

Tension and détente (2017–2021)

[edit]

The year 2017 saw a period of heightened tension between the U.S. and North Korea. Early in the year, the incoming U.S. President Donald Trump abandoned the policy of "strategic patience" associated with the preceding Obama administration. Later in the year, Moon Jae-in was elected President of South Korea with a promise to return to the Sunshine Policy.[126] On 4 July 2017, North Korea successfully conducted its first test of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), named Hwasong-14.[127] It conducted another test on 28 July.[128] On 5 August 2017, the UN imposed further sanctions which were met with defiance from the North Korean government.[129]

Following the sanctions, Trump warned that North Korean nuclear threats "will be met with fire, fury and frankly power, the likes of which the world has never seen before". In response, North Korea announced that it was considering a missile test in which the missiles would land near the U.S. territory of Guam.[130][131] North Korea conducted its sixth nuclear test on 3 September.[132] The test was met with international condemnation and resulted in further economic sanctions being taken against North Korea.[133] On 28 November, North Korea launched a further missile, which, according to analysts, would be capable of reaching anywhere in the United States.[134] The test resulted in the United Nations placing further sanctions on the country.[135]

In January 2018, the Vancouver Foreign Ministers' Meeting on Security and Stability on Korean Peninsula was co-hosted by Canada and the U.S., regarding ways to increase the effectiveness of the sanctions on North Korea.[136] The co-chairs (Canadian Foreign Minister Freeland and U.S. Secretary of State Tillerson) issued a summary that emphasized the urgency of persuading North Korea to denuclearize and emphasizing the need for sanctions to create conditions for a diplomatic solution.[137]

When Kim Jong Un proposed participating in the 2018 Winter Olympics in South Korea in his New Year's address, the Seoul–Pyongyang hotline was reopened after almost two years.[138] In February, North Korea sent an unprecedented high-level delegation to the Games, headed by Kim Yo-jong, sister of Kim Jong Un, and President Kim Yong-nam, which passed on an invitation to President Moon to visit the North.[139] Kim Jong Un and Moon met at the Joint Security Area on 27 April, where they announced that their governments would work toward a denuclearized Korean Peninsula and formalize peace between North and South Korea.[140] On 12 June, Kim met with Donald Trump at a summit in Singapore and signed a declaration, affirming the same commitment.[141] Trump announced that he would halt military exercises with South Korea and foreshadowed withdrawing American troops entirely.[142]

In September 2018, at a summit with Moon in Pyongyang, Kim agreed to dismantle North Korea's nuclear weapons facilities if the United States took reciprocal action. The two governments also announced that they would establish buffer zones on their borders to prevent clashes.[143] On 1 November, buffer zones were established across the DMZ to help ensure the end of hostility on land, sea and air.[144] The buffer zones stretched from the north of Deokjeok Island to the south of Cho Island in the West Sea and the north of Sokcho city and south of Tongchon County in the East (Yellow) Sea.[144][145] In addition, no fly zones were established along the DMZ.[144][145]

In February 2019 in Hanoi, a second summit between Kim and Trump broke down without an agreement.[146] On 30 June 2019, President Trump met with Kim Jong Un along with Moon Jae-in at the DMZ, making him the first sitting U.S. president to enter North Korea.[147] Talks in Stockholm began on 5 October 2019, between U.S. and North Korean negotiating teams, but broke down after one day.[148] On 16 June 2020, at approximately 2:49 p.m., the North Korean regime of Kim Jong-un blew up the North-South Joint Liaison Office in the Kaesong Industrial Complex.[149] In late 2021, President Moon, nearing the end of his five-year term, convened a forum, "Declaration of the End of the War: The Limitations and Prospects" continuing to seek a diplomatic breakthrough; but this was opposed by some speakers, including representatives of the People Power Party.[150]

The end of détente (2021–present)

[edit]

On 9 September 2022, North Korea passed a law to declare itself a nuclear weapons state.[151] In November 2022, a U.S.-South Korean air force exercise called Vigilant Storm was countered by missile tests and an air force exercise by North Korea.[152] In December 2022, five North Korean drones entered South Korean airspace, eluding South Korean defences, one entering the no-fly zone around the Blue House.[153] In late 2022, the South Korean National Intelligence Service began a series of raids targeting alleged North Korean spy-cells.[154]

As of 2023, North Korean publications remained censored in South Korea.[155] Meanwhile, North Korea campaigned against foreign culture, while the US government sponsored the flow of outside information into North Korea.[156]

On 5 January 2024, North Korea fired 200 shells towards Yeonpyeong Island.[157]

On 10 January 2024, during a speech to the Central Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea, Kim called for a "fundamental turnabout" in North Korea's stance towards South Korea, calling the South the "enemy".[158] He stated "the party’s comprehensive conclusion after reviewing decades-long inter-Korean relations is that reunification can never be achieved with those ROK riffraffs that defined the 'unification by absorption' and 'unification under liberal democracy' as their state policy", which he said is in "sharp contradiction with what our line of national reunification was: one nation, one state with two systems".[159]

Kim cited South Korean constitution's claims over the entire Korean Peninsula and South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol's policy towards the north as evidence that South Korea is an unsuitable partner for reunification.[158] He said the relations between the two Koreas currently were "states hostile to each other and the relations between two belligerent states" and no longer ones that are "consanguineous or homogeneous",[160] continuing by saying it is "unsuitable" to discuss the issue of reunification "with this strange clan [South Korea], who is no more than a colonial stooge of the U.S. despite the rhetorical word [we used to use] — 'the fellow countrymen'".[159]

Kim further confirmed a shift in policy in January 2024, when he gave a speech to the Supreme People's Assembly (SPA) calling for the constitution to be amended to remove references to cooperation and reunification, as well as specify DPRK's territorial borders and add an article specifying the ROK as the most hostile country.[161] He also rejected the maritime Northern Limit Line, saying that "If the Republic of Korea invades our ground territory, territorial air space, or territorial waters by even 0.001 mm, it will be considered a provocation of war". The SPA also voted on the abolition of three inter-Korean cooperation organizations; the Committee for the Peaceful Reunification of the Fatherland, the Korean People’s Cooperation Administration, and the Kumgangsan International Tourism Administration.[161]

One of the symbols of this was the destruction of the Arch of Reunification in Pyongyang on 23 January 2024.[162] Kim Jong-Un said at the 10th session of the 14th Supreme People’s Assembly of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: "We should also take steps such as the demolition of the "Monument to the Three Charters of National Reunification" which stands unceremoniously at the southern entrance to the capital, Pyongyang, in order to completely eliminate the very concepts of "reunification", "reconciliation" and "fratricidal" national history of the DPRK."[163] On 19 February 2024, North Korea has erased an image of the Korean Peninsula, viewed as a unification reference, from its major websites.[164]

On 1 March 2024, the government of President Yoon Suk Yeol plans to develop a new vision of unification with North Korea to include the principle of liberal democracy. South Korea plans to update its vision of unification for the first time in 30 years. This is the first revision of the Unification Formula of the national community, South Korea’s unification policy unveiled in August 1994 under the administration of late President Kim Young-sam.[165]

On 4 June 2024, South Korea's State Council suspended the 2018 Panmunjom Declaration due to border tensions over balloons carrying trash sent by North Korea.[166] On 9 June 2024, South Korea announced the resumption of loudspeaker broadcasts of anti-North Korean propaganda after the balloons were sent. Seoul's military detected around 330 balloons since 8 June 2024, with about 80 found in South Korean territory. The president's office stated that the broadcasts aimed to deliver messages of hope to the North Korean military and citizens. This response followed weeks of activists in the South launching balloons carrying K-pop, dollar bills, and anti-Kim Jong-un propaganda, which had infuriated Pyongyang. The loudspeaker broadcasts resumed after South Korea suspended the 2018 agreement, allowing for propaganda campaigns and potential military exercises near the border[167]

North Korea claims 1.4 million have enlisted after accusing South Korea of drone incursions. In response, Seoul is restricting leaflet activities near the border to prevent further escalation.[168][169]

North Korea's revised constitution now defines South Korea as a "hostile state," ending its pursuit of peaceful reunification and increasing military fortifications along the border.[170]

See also

[edit]- Cold War in Asia

- History of North Korea

- History of South Korea

- Korean reunification

- List of border incidents involving North and South Korea

- North Korea–South Korea relations

References

[edit]- ^ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 3.

- ^ a b Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 504. ISBN 0393327027.

- ^ a b Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0745633572.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 31–37. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 156–160. ISBN 0393327027.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 159–160. ISBN 0393327027.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 35–36, 46–47. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 48–49. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0824831745.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 50. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 50–51, 59. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 194–195. ISBN 0393327027.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 68. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 66, 69. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 255–256. ISBN 0393327027.

- ^ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0745633572.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 505–506. ISBN 0393327027.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 249–258. ISBN 0393327027.

- ^ a b Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ a b Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0824831745.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 247–253. ISBN 0393327027.

- ^ Stueck, William W. (2002). Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 71. ISBN 0691118477.

- ^ Jager, Sheila Miyoshi (2013). Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea. London: Profile Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-1846680670.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-0824831745.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 72, 77–78. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 86. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ a b c d Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0824831745.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 297–298. ISBN 0393327027.

- ^ Jager, Sheila Miyoshi (2013). Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea. London: Profile Books. pp. 237–242. ISBN 978-1846680670.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 81–82. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Jager, Sheila Miyoshi (2013). Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea. London: Profile Books. pp. 278–281. ISBN 978-1846680670.

- ^ a b Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0745633572.

- ^ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 8.

- ^ "Chronology of major North Korean statements on the Korean War armistice". News. Yonhap News Agency. 28 May 2009. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013.

- ^ "North Korea ends peace pacts with South". BBC News. 8 March 2013. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 206. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 493. ISBN 0393327027.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 208. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ "Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance between the People's Republic of China and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea". 11 July 1967. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 48. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ a b c Tan, Yvette (25 April 2018). "North and South Korea: The petty side of diplomacy". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ Wertz, Daniel; Oh, JJ; Kim, Insung (2015). The DPRK Diplomatic Relations (PDF) (Report). National Committee on North Korea. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2016.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 123. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 107, 116. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 93, 95–97. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 497. ISBN 0393327027.

- ^ Springer, Chris (2003). Pyongyang: the hidden history of the North Korean capital. Entente Bt. p. 125. ISBN 978-9630081047.

- ^ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0824831745.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Nguyen, Kham; Park, Ju-min (15 February 2019). "From comrades to assassins, North Korea and Vietnam eye new chapter with Trump-Kim summit". Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Jager, Sheila Miyoshi (2013). Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea. London: Profile Books. p. 366. ISBN 978-1846680670.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Jager, Sheila Miyoshi (2013). Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea. London: Profile Books. p. 371. ISBN 978-1846680670.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ Fraker, Sara E. (2009). The Oboe Works of Isang Yun. p. 27. ISBN 978-1109217803.

- ^ Larson, George A. (2001). Cold war shoot downs: Part two. Challenge Publications Inc.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0745633572.

- ^ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 158.

- ^ a b "Nuclear weapons and South Korea". The Korea Herald. 18 January 2023.

- ^ "아카이브 상세 | 강남 | 서울역사아카이브". museum.seoul.go.kr. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "아카이브 상세 | 강남 | 서울역사아카이브". museum.seoul.go.kr. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 42–45. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 210. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 59–66. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ "Minutes of Washington Special Actions Group Meeting, Washington, August 25, 1976, 10:30 a.m." Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State. 25 August 1976. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

Clements: I like it. It doesn't have an overt character. I have been told that there have been 200 other such operations and that none of these have surfaced. Kissinger: It is different for us with the War Powers Act. I don't remember any such operations.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (15 February 2004). "South Korean Movie Unlocks Door on a Once-Secret Past". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 September 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ Lee Tae-hoon (7 February 2011). "S. Korea raided North with captured agents in 1967". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ a b "[현장 속으로] 돌아오지 못한 북파공작원 7726명". 28 September 2013. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 76. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ Schaefer, Bernd (8 May 2017). "North Korea and the East German Stasi, 1987–1989". Wilson Center. Archived from the original on 15 February 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 113. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ "North Korea and Libya: Friendship through artillery | NK News". 5 January 2015. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016.

- ^ "North Korea Arms Libya". April 2011. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Young, Benjamin (30 March 2015). "Juche in the United States: The Black Panther Party's Relations with North Korea, 1969–1971". The Asia Pacific Journal. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016.

- ^ Farrell, Tom (17 May 2013). "Rocky road to Pyongyang: DPRK-IRA relations in the 1980s". NK News. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016.

- ^ Young, Benjamin R (16 December 2013). "North Korea: Opponents of Apartheid". NK News. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016.

- ^ Armstrong, Charles (April 2009). "Juche and North Korea's Global_Aspirations" (PDF). NKIDP Working Paper (1). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2016.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 129. ISBN 978-0415237499.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 47–49, 54–55. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 45–47. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 55–59. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ Jager, Sheila Miyoshi (2013). Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea. London: Profile Books. pp. 396–413. ISBN 978-1846680670.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ Jager, Sheila Miyoshi (2013). Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea. London: Profile Books. pp. 417–424. ISBN 978-1846680670.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 98–103. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 147–148. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 165. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0745633572.

- ^ John E. Findling; Kimberly D. Pelle (1996). Historical Dictionary of the Modern Olympic Movement. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 182–. ISBN 978-0313284779.

- ^ "Choi Duk Shin, 75, Ex-South Korean Envoy". The New York Times. Associated Press. 19 November 1989. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 173–176. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 509. ISBN 0393327027.

- ^ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 93.

- ^ Jager, Sheila Miyoshi (2013). Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea. London: Profile Books. p. 439. ISBN 978-1846680670.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 247. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 178. ISBN 0415237491.

- ^ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0745633572.

- ^ "South Korea Formally Declares End to Sunshine Policy". oice of America. 18 November 2010. Archived from the original on 12 April 2012.

- ^ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. vi. ISBN 978-0745633572.

- ^ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 138–143. ISBN 978-0745633572.

- ^ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. pp. 142–143.

- ^ "Backgrounder: How DPRK has condemned U.S.-S. Korea joint military exercises". Xinhua. 22 August 2016. Archived from the original on 23 August 2016.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 488–489, 494–496. ISBN 0393327027.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 61, 213. ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ Byrne, Leo (8 July 2016). "China, North Korea criticize new U.S. sanctions". NK News. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016.

- ^ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-0745633572.

- ^ "S. Korea raided North with captured agents in 1967". The Korea Times. 7 February 2011. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ K .J. Kwon (16 September 2013). "North and South Korea reopen Kaesong Industrial Complex". CNN. Archived from the original on 28 January 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ "South Korea to Halt Work at Joint Industrial Park With North". NBC News. 10 February 2016. Archived from the original on 10 February 2016.

- ^ "Leftist lawmaker gets 12-year prison term for rebellion plot". Yonhap News Agency. 17 February 2014. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ Sanger, David E; Broad, William J (4 March 2017). "Trump Inherits a Secret Cyberwar Against North Korean Missiles". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017.

- ^ Schiller, Markus; Hayes, Peter (9 March 2017). "Did cyber attacks slow down North Korea's missile progress?". NK News. Archived from the original on 9 March 2017.

- ^ Sherman, Paul; Haenle, Anne (12 September 2016). "The Real Answer to China's THAAD Dilemma". The Diplomat. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Ahn, JH (22 August 2016). "S.Korea to review possible new sites for THAAD deployment". NK News. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016.

- ^ "S. Korea unveils plan to raze Pyongyang in case of signs of nuclear attack". Yonhap News Agency. 11 September 2015. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016.

- ^ O'Carroll, Chad (10 February 2017). "Graphic, pro-North Korea leaflets found in downtown Seoul". NK News. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017.

- ^ Ahn, JH (14 February 2017). "New South Korean party accused of using Pyongyang's Juche Tower as logo". NK News. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017.

- ^ "South Korea: Government to pay defectors for North Korea secrets". Asian Correspondent. 5 March 2017. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017.

- ^ Sang-hun, Choe (10 October 2017). "North Korean Hackers Stole U.S.-South Korean Military Plans, Lawmaker Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017.

- ^ Sanger, David E.; Perlroth, Nicole (17 December 2014). "U.S. Said to Find North Korea Ordered Cyberattack on Sony". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014.

- ^ "South Korea's likely next president warns the U.S. not to meddle in its democracy". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2 May 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Choe, Sang-hun (4 July 2017). "North Korea Claims Success in Long-Range Missile Test". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ Choe, Sang-hun; Sullivan, Eileen (28 July 2017). "North Korea Launches Ballistic Missile, the Pentagon Says". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ "North Korea vows to retaliate against US over sanctions". BBC News. 7 August 2017. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017.

- ^ "North Korea considering firing missiles at Guam, per state media". Fox News. 8 August 2017. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017.

- ^ "Atom: Nordkorea legt detaillierten Plan für Raketenangriff Richtung Guam vor". Die.Welt.de. 10 August 2017. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ Collins, Pádraig (3 September 2017). "North Korea nuclear test: what we know so far". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ McGeough, Paul (12 September 2017). "North Korea: Sanctions tighten screws on regime but China, Russia get their way". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ David Wright (28 November 2017). "North Korea's Longest Missile Test Yet". The Equation. Union of Concerned Scientists. Archived from the original on 28 November 2017.

- ^ "Security Council Tightens Sanctions on Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Unanimously Adopting Resolution 2397 (2017)". United Nations. 22 December 2017. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ "Canada and United States to co-host Vancouver Foreign Ministers' Meeting on Security and Stability on Korean Peninsula". Global Affairs Canada. Office of the Minister of Foreign Affairs. 19 December 2017. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "Co-chairs' summary of the Vancouver Foreign Ministers' Meeting on Security and Stability on the Korean Peninsula". canada.ca. 16 January 2018. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018.

- ^ Kim, Hyung-Jin (3 January 2018). "North Korea reopens cross-border communication channel with South Korea". Chicago Tribune. AP. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ Ji, Dagyum (12 February 2018). "Delegation visit shows N. Korea can take "drastic" steps to improve relations: MOU". NK News. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ "Kim, Moon declare end of Korean (War". NHK World. 27 April 2018. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Everett (12 June 2018). "Document signed by Trump and Kim includes four main elements related to 'peace regime'". CNBC. Archived from the original on 14 November 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ Cloud, David S. (12 June 2018). "Trump's decision to halt military exercises with South Korea leaves Pentagon and allies nervous". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ "North Korea agrees to dismantle nuclear complex if United States takes reciprocal action, South says". ABC. 19 September 2018. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ a b c "Yonhap News Agency". Archived from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ a b Ji, Dagym (1 November 2010). "Two Koreas end military drills, begin operation of no-fly zone near MDL: MND". NK News. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "North Korea's foreign minister says country seeks only partial sanctions relief, contradicting Trump". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ "Donald Trump meets Kim Jong Un in DMZ; steps onto North Korean soil". USA Today. 30 June 2019. Archived from the original on 15 February 2021.

- ^ Tanner, Jari; Lee, Matthew (5 October 2019). "North Korea Says Nuclear Talks Break Down While U.S. Says They Were 'Good'". Time. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "North Korea's Wrecking of Liaison Office a 'Death Knell' for Ties With the South". The New York Times. 16 June 2020. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Chung, Chaewon (2 December 2021). "Speakers at Seoul forum question push for end-of-war declaration with DPRK". NK News.

- ^ "North Korea declares itself a nuclear weapons state". BBC News. 9 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ "North Korea flies 180 military aircraft near South Korean border as Seoul scrambles warplanes". ABC. 4 November 2022.

- ^ "N Korea drone entered S Korea's presidential no-fly zone: Army". Aljareera. 5 January 2023.

- ^ Bremer, Ifeng (13 February 2023). "ROK activist received North Korean orders while running for office: Lawmaker". NK News.

- ^ Weiser, Martin (12 January 2023). "South Korea upholds firewall against North". East Asia Forum.

- ^ Zwirko, Colin (16 January 2023). "North Korean museum targets drug use, K-pop in campaign against social ills". NK News.

- ^ AFP (5 January 2024). "North Korea fires artillery shells, evacuation order for South Korea island". Insider Paper. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ a b Seo, Heather (31 December 2023). "North Korea says it will no longer seek reunification with South Korea, will launch new spy satellites in 2024". CNN. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ a b Kim, Jeongmin (1 January 2024). "Why North Korea declared unification 'impossible,' abandoning decades-old goal". NK News. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ "Reunification with South? No, says North Korea's Kim Jong-un". South China Morning Post. dpa. 31 December 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ a b Zwirko, Colin; Kim, Jeongmin (16 January 2024). "North Korea to redefine border, purge unification language from constitution". NK News. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ Zwirko, Colin (23 January 2024). "North Korea demolishes symbolic unification arch, satellite imagery suggests". NK News - North Korea News. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ 한, 지숙 (16 January 2024). "김정은 "꼴불견"…철거 지시한 '조국통일3대헌장 기념비'는 무엇?". 헤럴드경제 (in Korean). Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ Soo-yeon, Kim (19 February 2024). "N. Korea erases image of Korean Peninsula from major websites". Yonhap News Agency. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ Wonju, Yi (1 March 2024). "S. Korea to update unification vision for 1st time in 30 years". Yonhap News Agency. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ "South Korea suspends a military deal with North Korea after tensions over trash balloons". AP News. 4 June 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ "South Korea to resume propaganda broadcasts after North sends hundreds more rubbish balloons | South Korea | The Guardian". The Guardian. 9 June 2024. Archived from the original on 9 June 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "North Korea claims 1 million youth enlist amid drone tensions". TRTWORLD. 16 October 2024. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ "North Korea says 1.4 million apply to join army amid tensions with South". Reuters. 15 October 2024. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ "North Korea says its revised constitution defines South Korea as 'hostile state' for first time". Independent. 17 October 2024. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Hoare, James; Pares, Susan (1999). Conflict in Korea: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0874369786.

External links

[edit]- Korean conflict

- Revolution-based civil wars

- Civil wars involving the states and peoples of Asia

- Foreign relations of South Korea

- Foreign relations of North Korea

- Territorial disputes of South Korea

- Territorial disputes of North Korea

- Korea–United States relations

- Korea–Soviet Union relations

- China–Korea relations

- North Korea–South Korea border

- Partition (politics)

- Aftermath of the Korean War

- Allied occupation of Korea

- North Korea–South Korea relations

- North Korea–United States relations

- Military history of North Korea

- Nuclear program of North Korea