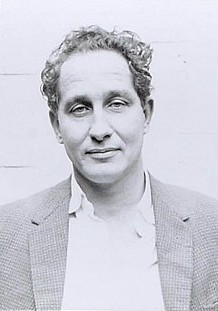

Ronnie Biggs

Ronnie Biggs | |

|---|---|

Buckinghamshire Constabulary mug-shot, 1964 | |

| Born | Ronald Arthur Biggs 8 August 1929 Stockwell, London, England |

| Died | 18 December 2013 (aged 84) Barnet, London, England |

| Occupation | Carpenter |

| Known for | Great Train Robbery of 1963 |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 5, including Michael Biggs |

| Motive | Financial gain/enjoyment[1] |

| Conviction(s) |

|

| Partner(s) |

|

Time at large | 35 years, 10 months |

| Escaped | 8 July 1965 |

| Escape end | 7 May 2001 |

Ronald Arthur Biggs (8 August 1929 – 18 December 2013) was an English criminal who helped plan and carry out the Great Train Robbery of 1963. He subsequently became notorious for his escape from prison in 1965, living as a fugitive for 36 years, and for his various publicity stunts while in exile. In 2001, Biggs returned to the United Kingdom and spent several years in prison, where his health rapidly declined. He was released from prison on compassionate grounds in August 2009[2] and died in a nursing home in December 2013.

Early life

[edit]Biggs was born in Stockwell, London, on 8 August 1929.[1] As a child during the Second World War, he was evacuated to Flitwick, Bedfordshire, and then Delabole, Cornwall.[3]

Career

[edit]In 1947, at age 18, Biggs enlisted in the Royal Air Force. He was dishonourably discharged for desertion two years later after breaking into a local chemist shop. One month after that, he was convicted of stealing a car and sentenced to prison. On his release, Biggs took part in a failed robbery attempt of a bookmaker's office in Lambeth, London. During his incarceration in HM Prison Wandsworth, he met Bruce Reynolds.[3]

After his third prison sentence, Biggs tried to go straight and trained as a carpenter. In February 1960, he married 21-year-old Charmian (Brent) Powell in Swanage,[4] the daughter of a primary school headmaster.[4] They had three sons together.[3][4]

Great Train Robbery

[edit]In 1963, Biggs, who needed money to fund a deposit on the purchase of a house for his family,[1] happened to be working on the house of a train driver who was about to retire. The driver has been variously identified as "Stan Agate", or because of his age, "Old Pete" or "Pop". The train driver's real name is unknown, since he was never caught. Biggs introduced the driver to the train robbery plot, which involved Reynolds.[5] Biggs was given the job of arranging for Agate to move the Royal Mail train after it had been waylaid.[1][3]

On the night of the hold up, Biggs told his wife he was off logging with Reynolds in Wiltshire.[4] The gang then stopped the mail train in the early hours of 8 August 1963, which was Biggs's 34th birthday.[6] Agate was unable to operate the main line diesel-electric locomotive because he had only driven shunting locomotives on the Southern Region.[7] Therefore, the driver of the intercepted train, Jack Mills, was coshed with an iron bar and forced to move the engine and mail carriages forward to a nearby bridge over a roadway, which had been chosen as the unloading point.[1] Biggs's main task had been to get Agate to move the train, and when it became obvious that the two were useless in that regard, they were banished to a waiting vehicle while the train was looted.[8]

When the men had unloaded 120 of the 128 mailbags from the train within Reynolds' allotted timetable, and returned to their hideout at Leatherslade Farm, various sources show that the robbery yielded the participants £2.6 million (equivalent to about £68.8 million in 2023); Biggs's share was £147,000 (equivalent to £3,888,100 in 2023).[9] With their timetable brought forward due to the police investigation closing in, Biggs returned home on the following Friday, with his stash in two canvas bags.[1]

After an accomplice failed to carry out his instructions to burn down Leatherslade Farm to destroy any evidence there,[1] Biggs's fingerprints were found on a tomato sauce bottle by Metropolitan Police investigators. Three weeks later, he was arrested in South London, along with 11 other members of the gang.[1] In 1964, nine of the 15-strong gang, including Biggs, were jailed for the crime. Most received sentences of 30 years.[1]

Escape and abscondment

[edit]Biggs served 15 months before escaping from Wandsworth Prison on 8 July 1965, scaling the wall with a rope ladder and dropping onto a waiting removal van.[10] He fled to Brussels by boat before sending a note to his wife to join him in Paris where he had acquired new identity papers and was undergoing plastic surgery.[1][6] During his time in prison, Charmian had started an extramarital relationship and was pregnant by the time of his escape to the Continent.[4] Choosing to support her husband, she had an illegal abortion in London and then travelled with their two sons to Paris to join Biggs.[4]

Australia

[edit]In 1966, Biggs fled to Sydney, where he lived for several months before moving to the seaside suburb of Glenelg in Adelaide, South Australia.[6] By the time Biggs and his family arrived in 1966, they had spent all but £7,000 (equivalent to £164,700 in 2023) of his £147,000 share of the train robbery proceeds: £40,000 (equivalent to £941,200 in 2023) on plastic surgery in Paris; £55,000 (equivalent to £1,294,100 in 2023) paid as a package deal to get him out of the UK to Australia; and the rest on legal fees and expenses.[1][4]

In 1967, just after their third child was born, Biggs received an anonymous letter from Britain telling him that Interpol suspected that he was in Australia and that he should move. In May 1967, the family moved to Melbourne, where he rented a house in the suburb of Blackburn North while his wife Charmian and their three sons lived in Doncaster East. Biggs had a number of jobs in Melbourne before undertaking set construction work at the GTV Channel 9 Television City studios. In October 1969, a newspaper report by a Reuters correspondent revealed that Biggs was living in Melbourne and claimed that police were closing in on him. The story led the evening news bulletin at Channel 9 and Biggs fled his home, staying with family friends in the outer eastern suburbs of Melbourne. Five months later, he fled on a passenger liner from the Port of Melbourne, using the altered passport of a friend; his wife and sons remained in Australia. Twenty days later, the ship berthed in Panama and within two weeks Biggs had flown to Brazil.[6]

Following disclosure of Biggs' fathering a child in Brazil, Charmian agreed to a divorce in 1974, which was completed in 1976.[4] Allowed by authorities to remain in Australia, she reverted to her maiden name of Brent and sold her story for £40,000 to an Australian media group to enable her to purchase the rented house that the family had lived in at the time of Biggs's flight to Brazil.[4] Charmian later undertook a degree and became an editor, publisher and journalist. Her sons—who later visited Biggs a few times in Brazil—live anonymously. In 2012, Charmian was a consultant on the five-part ITV Studios docu-drama Mrs Biggs, which recounts the couple's time from first meeting to Biggs's flight to Brazil.[4]

Rio de Janeiro

[edit]In 1970, when Biggs arrived in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil did not have an extradition treaty with the United Kingdom.[10] In 1971, Biggs's eldest son, Nicholas, aged 10, died in a car crash[11] in Melbourne.[12]

In 1974, Daily Express reporter Colin MacKenzie received information suggesting that Biggs was in Rio de Janeiro; a team consisting of MacKenzie, photographer Bill Lovelace and reporter Michael O'Flaherty confirmed this and broke the story. Scotland Yard detective Jack Slipper arrived soon afterwards, but Biggs could not be extradited because his girlfriend, nightclub dancer Raimunda de Castro, was pregnant. Brazilian law at the time did not allow a parent of a Brazilian child to be extradited.[13]

During 1974, in Rio, Biggs, an avid jazz fan, collaborated with Bruce Henri (an American double bass player), Jaime Shields, and Aureo de Souza to record Mailbag Blues, a musical narrative of his life that he intended to use as a movie soundtrack. This album was left undiscovered until it was finally released in 2004 by whatmusic.com.[14]

In April 1977, Biggs attended an informal drinks party on board the Royal Navy frigate HMS Danae (F47), which was in Rio for a courtesy visit, but he was not arrested.[11] Though in Brazil he was safe from extradition, Biggs's status as a known criminal meant he could not work, visit bars or be away from home after 10 p.m.[15] To provide an income, Biggs's family hosted barbecues at his home in Rio, where tourists could meet Biggs and hear him recount his involvement in the robbery, which, in fact, was minor. Biggs was even visited by former footballer Stanley Matthews, whom Biggs afterwards invited to his apartment after hearing that he was in Rio. "We had tea on the small balcony at the rear of his home, and one of the first things he asked was, 'How are Charlton Athletic doing?' It turned out he had supported Charlton from being a small boy and had often seen me play at The Valley."[16] Around this time, "Ronnie Biggs" mugs, coffee cups and T-shirts also appeared throughout Rio.

Biggs recorded vocals on two songs for The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle, Julien Temple's film about the Sex Pistols. The basic tracks for "No One is Innocent" (a.k.a. "The Biggest Blow (A Punk Prayer)"/"Cosh The Driver") and "Belsen Was a Gas" were recorded with guitarist Steve Jones and drummer Paul Cook at a studio in Brazil shortly after the Sex Pistols' final performance, with overdubs added in an English studio at a later date. "No One is Innocent" was released as a single in the UK on 30 June 1978 and reached number 7 in the UK Singles Chart. The sleeve showed a British actor dressed as Nazi leader Martin Bormann playing bass with the group.

In March 1981, Biggs was kidnapped by a gang of British ex-soldiers. The boat they took him aboard suffered mechanical problems off Barbados, and the stranded kidnappers and Biggs were rescued by the Barbados coastguard and towed into port in Barbados. The kidnappers hoped to collect a reward from the British police; however, like Brazil, Barbados was found to have had no valid extradition treaty with the United Kingdom (a fact which chess player David Levy claimed to have paid lawyers to unearth)[17] and Biggs was sent back to Brazil.[18][19] In February 2006, Channel 4 aired a documentary featuring dramatisations of the attempted kidnapping and interviews with John Miller, the ex-British Army soldier who carried it out. The team was headed by security consultant Patrick King. In the documentary, King claimed that the kidnapping may have been a deniable operation.[20] The ITN reporter Desmond Hamill paid to accompany Biggs on the private Learjet returning him to Brazil and secured an exclusive interview, as well as convincing Biggs to kiss the tarmac upon landing.[21] The kidnapping attempt was the subject of the film Prisoner of Rio (1988), which was co-written by Biggs. In the film, Biggs was played by Paul Freeman.

Biggs's son by de Castro, Michael Biggs, was seven years old when he became a member of the highly successful[22] Brazilian children's programme and music band Balão Mágico (1982–1986),[22][23] bringing relative financial security to his father.[22]

In 1991, Biggs sang vocals for the songs "Police on My Back" and "Carnival in Rio" by German punk band Die Toten Hosen. In 1993, Biggs sang on three tracks for the album Bajo Otra Bandera by Argentinian punk band Pilsen.[24][25]

In 1993, Slipper travelled once more to Rio on a private mission to try to persuade Biggs to come home voluntarily, which failed.[26] In 1994 the German journalist Ulli Kulke managed to bring both Biggs and Slipper together in a telephone interview. In this interview the two antagonists talk about their encounters in 1974 and 1993. The Interview was first published (in German) in 1994 in the German weekly Wochenpost and reprinted in the daily newspaper Die Welt in 2013 on the occasion of Biggs' death.[27]

In 1997 the UK and Brazil ratified an extradition treaty. Two months later, the UK government made a formal request to the Brazilian government for Biggs's extradition. Biggs had stated that he would no longer oppose extradition.[13] English lawyer Nigel Sangster QC travelled to Brazil to advise Biggs. The extradition request was rejected by the Brazilian Supreme Court, giving Biggs the right to live in Brazil for the rest of his life.[28]

Return to the United Kingdom

[edit]In 2001 Biggs announced to The Sun newspaper that he would be willing to return to the UK.

Imprisonment

[edit]Having 28 years of his sentence left to serve, Biggs was aware that he would be detained upon arrival in Britain. His trip back to Britain on a private jet was paid for by The Sun newspaper, which reportedly paid Michael Biggs £20,000 plus other expenses [according to whom?] in return for exclusive rights to the news story. Biggs arrived on 7 May 2001, whereupon he was immediately arrested and re-imprisoned.[6]

His son Michael said in a press release that, contrary to some press reports, Biggs did not return to the UK simply to receive health care which was not available in Brazil, and he had friends who would have contributed to such expenses,[29] but that it was his desire to "walk into a Margate pub as an Englishman and buy a pint of bitter".[30] John Mills, son of train driver Jack Mills, was unforgiving: "I deeply resent those, including Biggs, who have made money from my father's death. Biggs should serve his punishment."[31] Mills never fully recovered from his injuries sustained during the robbery. He died of an unrelated cause (leukaemia) in 1970.[32][33]

On 14 November 2001, Biggs petitioned Governor Hynd of HMP Belmarsh for early release on compassionate grounds based on his poor health. He had been treated four times at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, London, in less than six months. His health was deteriorating rapidly, and he asked to be released into the care of his son for his remaining days.[34] The application was denied. On 10 August 2005, it was reported that Biggs had contracted MRSA. His representatives, seeking for his release on grounds of compassion, said that their client's death was likely to be imminent.[35] On 26 October 2005, Home Secretary Charles Clarke declined his appeal, stating that his illness was not terminal. Home Office compassion policy is to release prisoners with three months left to live.[36] Biggs was claimed by his son Michael to need a tube for feeding and to have "difficulty" speaking.

On 4 July 2007, Biggs was moved from Belmarsh Prison to Norwich Prison on compassionate grounds.[37] In December, Biggs issued a further appeal, from Norwich Prison, asking to be released to die with his family: "I am an old man, and often wonder if I truly deserve the extent of my punishment. I have accepted it, and only want freedom to die with my family and not in jail. I hope Mr. Straw decides to allow me to do that. I have been in jail for a long time, and I want to die a free man. I am sorry for what happened. It has not been an easy ride over the years. Even in Brazil, I was a prisoner of my own making. There is no honour to being known as a Great Train Robber. My life has been wasted."[38]

In January 2009 a series of strokes were said to have rendered him unable to speak or walk. His son Michael had also claimed that the Parole Board might bring the release date forward to July. On 13 February that year, it was reported that Biggs had been taken to hospital from his cell at Norwich Prison, suffering from pneumonia.[39][40][41] This was confirmed the following day by his son Michael, who said Biggs had serious pneumonia but was stable.[42] News of his condition prompted fresh calls from his son Michael for his release on compassionate grounds.[43]

On 23 April 2009, the Parole Board recommended that Biggs be released on 4 July,[44] having served a third of his 30-year sentence. However, on 1 July, Straw did not accept the Parole Board's recommendation and refused parole, stating that Biggs was 'wholly unrepentant'.[2] On 28 July, Biggs was readmitted to Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital with pneumonia. He had been admitted to the same hospital a month earlier, with a chest infection and a fractured hip, but returned to prison on 17 July. His son Michael said, in one of his frequent news releases: "It's the worst he's ever been. The doctors have just told me to rush there."[45]

On 30 July, it was claimed by representatives of Biggs that he had been given "permission" to challenge the decision to refuse him parole. However, the Home Office stated only that "an application for the early release on compassionate grounds of a prisoner at HMP Norwich" had been received by the public protection casework section in the National Offender Management Service.[46] Biggs was released from custody on 6 August 2009, two days before his 80th birthday, on "compassionate grounds".[47]

Later life

[edit]Following his release from prison, Biggs's health improved, leading to suggestions that he might soon be moved from hospital to a nursing home. In response to claims that Biggs's state of health had been faked, his lawyer stated, "This man is going to die, there is going to be no Lazarus coming back from the dead, he is ill, he is seriously ill." However, Biggs himself stated, "I've got a bit of living to do yet. I might even surprise them all by lasting until Christmas, that would be fantastic."[48]

On 29 May 2010, Biggs was again admitted to hospital in London after complaining of chest pain. He underwent tests at Barnet Hospital. His son Michael stated, "he's conscious but he's in a lot of pain". In August 2010, it was claimed by the Sunday Mirror that Biggs would be attending a gala dinner where he would be collecting a lifetime achievement award for his services to crime.

On 10 February 2011, Biggs was admitted to Barnet Hospital with another suspected stroke. His son Michael said he was conscious and preparing to have a CT scan and a series of other tests to determine what had happened.[49] On 17 November 2011, Biggs launched his new and updated autobiography, Ronnie Biggs: Odd Man Out – The Last Straw, at Shoreditch House, London.[1] He was unable to speak and used a word board to communicate with the press.[50]

On 12 January 2012, ITV Studios announced it had commissioned a five-part drama, Mrs Biggs, to be based around the life of Biggs's wife Charmian, played by Sheridan Smith and Biggs by Daniel Mays. Charmian Biggs acted as a consultant on the series and travelled to Britain from Australia to visit Biggs in February 2012, just before filming for Mrs Biggs.[51][52]

In March 2013, Biggs attended the funeral of fellow train robber, Bruce Reynolds.[53] In July 2013, The Great Train Robbery 50th Anniversary: 1963–2013 was published, with input from Biggs and Reynolds.

Death

[edit]On 18 December 2013, aged 84, Biggs died at the Carlton Court Care Home in Barnet, North London, where he was being cared for.[54][55] His death coincidentally occurred hours before the first broadcast of a two-part BBC television series, The Great Train Robbery, in which Biggs was portrayed by actor Jack Gordon.[56] Biggs's body was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium on 3 January 2014. The coffin was covered with the Union Flag, the flag of Brazil and a Charlton Athletic scarf. An honour guard of British Hells Angels escorted his hearse to the crematorium.[57] The Reverend Dave Tomlinson officiated at Biggs's funeral, for which he drew public criticism; Tomlinson responded to critics by using the Bible verse "Judge not, that ye be not judged".[58]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Ronnie Biggs & Chris Packard (17 November 2011). Odd Man Out – The Last Straw. M Press. ISBN 978-0957039827.

- ^ a b c "Train robber Biggs wins freedom". BBC News. 6 August 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Obituary: Ronnie Biggs". BBC News. 18 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Claire Webb (5 September 2012). "The first Mrs Biggs: "I'd do it all again"". Radio Times. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ "QI Series G - Greats". British Comedy Guide. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Life and Crimes of Ronnie Biggs: from Brazil to Belmarsh August 2009, The Guardian. Retrieved March 2011

- ^ "The day crime gang stopped a train and shocked the world". Nottingham Post. 6 August 2013. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Moore, Patrick H. "Dead Legends File – Ronnie Biggs the Great Train Robbery Rogue, Checks Out at Last". All Things Crime. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Chapman, Peter (18 December 2013). "Ronnie Biggs, train robber, 1929–2013". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ a b "BBC NEWS - UK - Profile: Ronnie Biggs".

- ^ a b "Biggs family vow to fight on". Archived from the original on 9 August 2009.

- ^ Mrs Biggs

- ^ a b UK asks for extradition of Ronnie Biggs 30 October 1997, BBC. Retrieved August 2011

- ^ "WhatMusic.com official site". WhatMusic.com. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- ^ Prisoner in Paradise. Weekly World News. 8 August 1989.

- ^ Matthews, Stanley. The Way It Was: My Autobiography, Headline, 2000 (ISBN 0747271089)

- ^ "Kingpin Chess Magazine » The Chess Player and the Train Robber". www.kingpinchess.net. 18 December 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ "From the archive, 25 March 1981: Kidnapping of Ronnie Biggs ends in farce". guardian.com. 25 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ Muello, Peter (5 October 1997). "Great Train Robber on the Lam in Brazil Finds British Lion on Trail". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "Kidnap Ronnie Biggs- Documentary". Channel 4. 9 February 2006. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- ^ Daily Telegraph Obituary. Retrieved 3 May 2013

- ^ a b c "Michael Biggs: The end of the line for a dutiful son?". The Independent. 11 April 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "My father Ronnie Biggs". The Guardian. 24 August 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "Mi papá es un punk" (in Spanish). pagina12. 4 May 2006. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- ^ "Pil Trafa y Ronald Biggs" (in Spanish). BlogSpot.com. 7 March 2009. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (18 December 2013). "The Guardian: Ronnie Biggs obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Ronnie Biggs und der Inspektor: Ein Gespräch wie unter guten alten Kumpels - WELT".

- ^ "Fraud & financial Regulation QC - Leeds QC - Fraud QC Leeds".

- ^ "Statement from Michael Biggs =PR Newswire". Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ "2001: Biggs wants to return". The Sun. London. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Kim Sengupta "After 36 years on the run, Biggs is back where he belongs: in jail", The Independent, 8 May 2001

- ^ "Flashback: The Great Train Robbery".

- ^ "Biggs in hospital 'after stroke'". BBC News. 10 February 2011.

- ^ "My beloved dad, the train robber". The Guardian. 17 January 2004. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ "Release appeal as Biggs has MRSA". BBC News. 4 July 2007.

- ^ "Plea to release Ronnie Biggs rejected". Ulster Television. 26 October 2005. Archived from the original on 7 January 2006.

- ^ "Biggs moved from Belmarsh prison". BBC News. 4 July 2007.

- ^ Jonathan Owen; Sadie Gray (30 December 2007). "Ronnie Biggs pleads: Let me out so I can die with my family". Independent on Sunday. London.

- ^ "Ronnie Biggs Is Taken To Hospital". Yahoo News. 13 February 2009. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ "Ronnie Biggs Is Taken To Hospital". Sky News. 13 February 2009. Archived from the original on 13 August 2009. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ "Train robber Biggs hospitalised". BBC. 13 February 2009. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ "Train robber Biggs has pneumonia". BBC. 14 February 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ "Ronnie Biggs: Son Michael pleads for the release of great train robber". The Daily Telegraph. London. 15 February 2009. Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ Ford, Richard; Fresco, Adam (23 April 2009). "Ronnie Biggs recommended for early release". The Times. London. Retrieved 22 May 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Train Robber Biggs has Pneumonia BBC. 28 July 2009

- ^ Biggs to Challenge Parole Refusal BBC Online 30 July 2009

- ^ Burns, John (7 August 2009). "Britain's Great Train Robber Freed". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- ^ "Great Train Robber Ronnie Biggs in hospital". www.telegraph.co.uk. 29 May 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Ronnie Biggs admitted to hospital with a suspected stroke BBC. 10 February 2011

- ^ "Ronnie Biggs Details 'Regrets' In New Book". 17 November 2011.

- ^ Page 18/19 of the ITV press pack

- ^ The two Mrs Biggs. ITV, 4 September 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ "Bruce Reynolds funeral: Ronnie Biggs attends Great Train Robber's sendoff". the Guardian. 20 March 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ "Obituary: Ronnie Biggs". BBC News. 18 December 2013.

- ^ "Great Train Robber Ronnie Biggs dies aged 84". BBC News UK. 18 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ Withnall, Adam (18 December 2013). "Ronnie Biggs dead: Great Train Robbery fugitive dies aged 84". The Independent. London. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ "Great Train Robber Ronnie Biggs's funeral takes place". BBC News. 3 January 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ Sherwin, Adam (10 January 2014). "Ronnie Biggs was an 'extraordinary' man, says the unrepentant Reverend". The Independent. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

External links

[edit]- Guardian photo gallery of Biggs

- "The Big One: Ronald Biggs and the Great Train Robbery", Crime Library

- Obituary at the Daily Telegraph

- Ronald Arthur (Ronnie) Biggs, Great Train Robber, died on December 18th, aged 84 The Economist, Obituary, 4 January 2014.

- 1929 births

- 2013 deaths

- 20th-century British criminals

- 20th-century Royal Air Force personnel

- British expatriates in Australia

- British expatriates in Brazil

- British people convicted of theft

- Criminals from London

- English autobiographers

- English escapees

- English punk rock singers

- Escapees from England and Wales detention

- Golders Green Crematorium

- Great Train Robbers

- Great Train Robbery (1963)

- People from Lambeth

- Inmates of HM Prison Belmarsh

- Sex Pistols

- Royal Air Force airmen