Pomerium

The pomerium or pomoerium was a religious boundary around the city of Rome and cities controlled by Rome. In legal terms, Rome existed only within its pomerium; everything beyond it was simply territory (ager) belonging to Rome.

Etymology

[edit]The term pōmērium is a classical contraction of the Latin phrase post moerium (lit. 'behind/beyond the wall'). The Roman historian Livy writes in his Ab Urbe Condita that, although the etymology implies a meaning referring to a single side of the wall, the pomerium was originally an area of ground on both sides of city walls. He states that it was an Etruscan tradition to consecrate this area by augury and that it was technically unlawful to inhabit or to farm the area of the pomerium, which in part had the purpose of preventing buildings from being erected close to the wall (although he writes that, in his time, houses were in fact built against the wall on the line).[1] Other writers suggest a derivation from prō moerium, "against the wall".[2][3]

Location and extensions

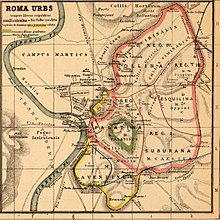

[edit]Tradition maintained that the pomerium was the original line ritually ploughed by Romulus around the walls of the original city and that it was expanded by Servius Tullius. The legendary date of its demarcation, 21 April, continued to be celebrated as the anniversary of the city's founding.[4]

The pomerium did not follow the line of the Servian walls, and remained unchanged until the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla, in a demonstration of his absolute power, expanded it in 80 BC. Several white marker stones (known as "cippi") commissioned by Claudius have been found in situ and several have been found away from their original location. These stones mark the boundaries and relative dimensions of the pomerium extension by Claudius. This extension is recorded in Tacitus and outlined by Aulus Gellius.[5] The latest pomerial stone from the reign of Claudius was discovered on 17 June 2021 in the vicinity of the Mausoleum of Augustus.[6]

The pomerium was not a walled area, but rather a legally and religiously defined one marked by cippi. It encompassed neither the entire metropolitan area nor even all the Seven Hills (the Palatine Hill was within the pomerium, but the Capitoline and Aventine Hills were not). The Curia Hostilia and the well of the Comitium in the Forum Romanum, two extremely important locations in the government of the city-state and its empire, were located within the pomerium, while the Temple of Bellona was beyond the pomerium.

Associated restrictions

[edit]Pomerium represented a sacred boundary. According to Livy, violating the pomerium was akin to stretching the human body too far.[7]

- The magistrates who held imperium did not have full power inside the pomerium. They could have a citizen beaten, but not sentenced to death. This was symbolised by removing the axes from the fasces carried by the magistrate's lictors.[8] Only a dictator's lictors could carry fasces containing axes inside the pomerium.

- It was forbidden to bury the dead inside the pomerium. During his life, Julius Caesar received in advance the right to a tomb inside the pomerium, but his ashes were actually placed in his family tomb.[9] However, Trajan's ashes were interred after his death in AD 117 at the foot of his Column,[10] which was within the pomerium.[9]

- Provincial promagistrates and generals were forbidden from entering the pomerium, and resigned their imperium immediately upon crossing it (as it was the superlative form of the ban on armies entering Italy). Ceremonies of triumph, in which an army would march through the city in celebration of a victory, were an exception to this rule, although a general could only enter the city on the very day of his triumph, and would be required to wait outside the pomerium with his troops until that moment.[9] Under the Republic, soldiers also lost their status when entering, becoming citizens: thus soldiers at their general's triumph wore civilian dress.[citation needed] The Comitia Centuriata, one of the Roman assemblies, consisting of centuriae (voting units, but originally military formations within the legions), was required to meet on the Campus Martius outside the pomerium. Similarly to the triumph, the Roman ovation also allowed a general to cross the pomerium without losing rank, but generally he could not bring his soldiers and had to enter on foot rather than on a chariot led by white horses.

- The Theatre of Pompey, where Julius Caesar was murdered, was outside the pomerium and included a chamber where the Senate could meet allowing the attendance of any senators who were forbidden to cross the pomerium and thus would not have been able to meet in the Curia Hostilia.

- Weapons were prohibited inside the pomerium. Praetorian Guards were allowed in only in civilian dress (toga), and were then called collectively cohors togata. But it was possible to sneak in daggers (the proverbial weapon for political violence; see sicarius). Since Julius Caesar's assassination occurred outside this boundary, the senatorial conspirators could not be charged with sacrilege for carrying weapons inside the sacred city.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, I.44

- ^ Oliver, James Henry (11 March 1932). "The Augustan pomerium ..." Italy – via Google Books.

- ^ Academy, British. Bd.4 Glossaria Latina. Georg Olms Verlag. ISBN 9783487400914 – via Google Books.

- ^ Pomerium, Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ Tacitus, Annales, XII, 24; Noctes Atticae, XIII, 14, 7.

- ^ "Rare stone discovered outlining ancient Rome's city limits"

- ^ Sennett 1996, p. 108.

- ^ Gaughan, Judy E. (2010). Murder Was Not a Crime: Homicide and Power in the Roman Republic. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0292779921.

- ^ a b c Beard, Mary; North, John; Price, Simon (1998). Religions of Rome Volume 1: A History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 177–180. ISBN 978-0-521-31682-8.

- ^ Epitome de Caesaribus 13.11; Eutropius 8.5[usurped].

Bibliography

[edit]- Sennett, R. (1996). "The creation of a Roman city". Flesh and Stone: The Body and the City in Western Civilization. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-34650-3. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

External links

[edit]- Samuel Ball Platner, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome: Pomerium

- Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities: Pomoerium

- Transactions of the American Philological Association Alternate etymology: pro-murium